Four Things To Read

Why the Most Educated People in America Fall for Anti-Semitic Lies, by Dara Horn: “The problem was not that Jewish students on American university campuses didn’t want free speech, or that they didn’t want to hear criticism of Israel. Instead, they didn’t want people vandalizing Jewish student organizations’ buildings, or breaking or urinating on the buildings’ windows. They didn’t want people tearing their mezuzahs down from their dorm-room doors. They didn’t want their college instructors spouting anti-Semitic lies and humiliating them in class. They didn’t want their posters defaced with Hitler caricatures, or their dorm windows plastered with Fuck Jews. They didn’t want people punching them in the face, or beating them with a stick, or threatening them with death for being Jewish. At world-class American colleges and universities, all of this happened and more.” This is a really important essay! You can disagree, as I do, with some of Horn’s positions on Israel and Zionism—which, importantly, do not include giving Israel a pass on its actions in Gaza—but you should take very seriously the core of her argument, which is a meditation on this statement, “It remains unclear why anti-Semitism should matter only when it is lethal, or if so, how many unambiguously anti-Semitic murders would be necessary for anti-Semitism to be happening outside whiny Jews’ heads.” Horn’s writing is, in many places, angry, sarcastic, and satirical, but her analysis is largely spot on.

Anti-Judaism: The Western Tradition, by David Nirenberg: I’m pretty sure I’ve told you about this book before, but I am including it here because Horn uses it in her article. This is what she says: “Nirenberg’s argument…is that Western cultures…have often defined themselves through their opposition to what they consider ‘Judaism.’ This has little to do with actual Judaism [or actual Jewish people], and a lot to do with whatever evil these non-Jewish cultures aspire to overcome…If piety was a given society’s ideal, Jews were impious blasphemers; if secularism was the ideal, Jews were backward pietists. If capitalism was evil, Jews were capitalists; if communism was evil, Jews were communists. If nationalism was glorified, Jews were rootless cosmopolitans; if nationalism was vilified, Jews were chauvinistic nationalists. ‘Anti-Judaism’ thus becomes a righteous fight to promote justice.” Horn’s account of how this plays out in modern times—and, in particular, in how people respond to Jews in the context of Hamas’ October 7th attack and Israel’s response in Gaza—makes for chilling reading.

Black English Doesn’t Have to Be Just for Black People, by John McWhorter: “There is simply no way that whiteness and Blackness will mingle as they have in music, cuisine, gesture, greeting styles, dating, matrimony and multiracial identity, and yet for some reason be halted at language. One might wish to enforce an artificial kind of blockade here, but it’s far too late. The horse has been out of the barn ever since white kids embraced Jay-Z and Tupac.” McWhorter is an African American linguist who teaches at Columbia University, and he has a point. Language change has very little to do with the arbitrary rules we construct around its usage, whether as grammatical prescriptions, like the one that says you can’t use they/them as second person pronouns, or prescriptions about who is “allowed” to use which variety of English, or which vocabulary. There is a difference between claiming that something is or is not allowed and insisting that people should be held accountable for the language they use and how they use it. That’s the part that I think McWhorter leaves out of this essay. By starting with a truth about language change and not really considering the full cultural and political context of that change, I think he ends up with a simplistic, if not reductive conclusion.

Do You Pay?, by Allison K Williams: “Fundamentally, every [literary] journal has the right to choose the payment policy that’s best for their mission. Maybe they want to pay in the future; maybe it will always be about self-promotion or joining a literary community. But when a magazine elides their lack of cash compensation or makes it hard to find, they insinuate it should not be the writer’s concern, or a criterion for submission. It becomes another subtle signpost to writers: Your work shouldn’t be for money. At its worst, not actively sharing the information says, you shouldn’t care, writer. You shouldn’t ask. As if it’s money-grubbing or disgraceful or besmirching the purity of the art.” If you’re a writer who submits to literary journals, this essay is well worth reading.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

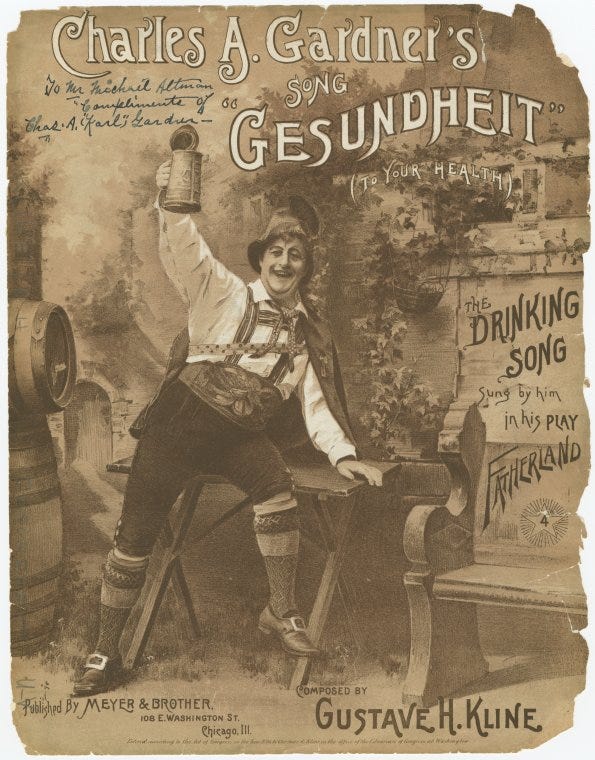

These are from the New York Public Library’s collection of sheet music of American popular songs.

All Aboard For Podunk

Gesundheit (To Your Health)

Bright Eyes

Lovers Once But Strangers Now or Strangers Now But Lovers Once

Four Things To Listen To

Insurreal - Transgressive

This is the latest release by my son’s death metal band.

Yiddish Socialists and the Garment Industry

A very interesting history of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, but also a look at what unions are and what they can accomplish when they are as concerned with union values as they are with fair compensation and safe workplaces.

Barcelona Gipsy Klezmer Orchestra - Hévenu Shalom Aléchem

Igor Stravinsky - Symphony of Psalms: III. Psalm 150 (Entire)

Four Things About Me

I do not remember the name of the professor who taught the writing class that was, back in the 1980s, the first class I was required to take as an English major at Stony Brook University, but I believe he had come to Stony Brook from Yale, and I remember very clearly his first-day lecture about how college students no longer knew what it meant to write a persuasive essay, much less do literary analysis, and that none of us, therefore, should expect to get an A in his class. The only other thing I remember from that class is that he gave me the A he said would be impossible to achieve. (I don’t know if anyone else did, though I assume I wasn’t the only one.)

From that class on, until my junior year, I never received anything less than an A- on any paper I wrote, regardless of the discipline. Then, in my junior year, I took a course in the modern novel with Professor Sallie Sears. The first book we read that year was André Gide’s The Immoralist. I do not remember the specific prompt to which I was responding when I handed in the first paper of that semester, but it was about five pages long, had to do with the letter that frames the novel, and I handed it in with the same confidence as when I handed any other paper in: that I had done a good job and that I would, of course, receive an A. You can imagine my shock, then, when I got my paper back, covered in Professor Sears’ tiny red handwriting, with a big C- on the cover. I was incredulous. Clearly, I thought—and I have seen this response over the years in not a few of my own students who have been similarly full of themselves—she had failed to understand the full sophistication of my argument. After discussing my paper with her during her office hours, however, I understood full well that the failure had been mine, that my writing was not as strong as I had believed—and, to be honest, as all of the professors I’d had to that point had led me to believe. Professor Sears gave me an opportunity to rewrite the paper, which I did. Five pages grew to fifteen pages and—I have a scan of the essay on my hard drive right now—my grade went from a C- to an A- of which I was extremely proud, because I knew that I had earned it in a way I had not earned any of the grades I’d previously received. I remain immensely grateful to Professor Sears. That was the semester I began truly to learn how to write.

When I was younger, I looked a lot older than my age. I was the guy, when my friends and I were 16, who could walk into a deli and buy a six-pack of beer, no questions asked. (The drinking age was eighteen back then.) I never drank with the friends I bought the beers for—I didn’t start liking the taste of beer till I was well into my twenties—but I was happy to do it for them. Often enough when I was a teenager that we would anticipate it, because my mother always looked younger than her age, waitstaff in restaurants would assume we were out on a date, that I was old enough to drink, and would treat us accordingly, asking if I “and the lady” wanted to start off with cocktails or bringing me the check at the end of the meal. Once, when me, my mother, and my sisters went to get a family picture taken—probably to JC Penny or some such place—the photographer actually thought my mother and I were husband and wife, and my sisters were our children. One incident that was just about me, though, took place during my freshman year of college. My dorm threw a keg party. I was standing at the door to the room where the beers were being poured, when a women I recognized from freshman orientation got in line. We’d exchanged a few words during orientation, so, when she struck up a conversation, I thought it was because she remembered me. She was smart, and funny, and very cute. Then, out of nowhere, she asked me, “What subject do you teach here?” I was floored. She had mistaken me for a faculty member, not even a graduate student, but a full-fledged professor. When I reminded her that we’d met at orientation, by way of explaining her mistake, she said, “I’m so sorry! It must have been the low light and your glasses.” Then she made some excuse about needing to get back to her room and left the party. We never spoke again.

I have a copy of Tennyson’s In Memorium that my friend Nuria gave me at the end of the summer of 1985. We’d both been studying Scottish literature at Edinburgh University as part of the Scottish Universities International Summer School, and it was time for us to go home, her to Spain, me back here to the States. She’d found the book in a used bookstore. Its first owner, Jessie Black, had dated it April 14th 1885, just a few months short of exactly 100 years earlier. It’s now 39 years later, and I still page through the book once in a while and read one or two of the poems Tennyson wrote in memory of his friend, Arthur Henry Hallam, though the sequence ultimately moves far beyond Hallam’s death in the subjects it explores. The summer of 1985 was formative for me in ways that went far beyond what I learned about Scottish literature. There were many reasons, I suppose, but Nuria’s friendship was a very important one, which is why I treasure this book.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Photo of #4 by Kin Shing Lai on Unsplash.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion