Four Things To Read

Two more books by people I know that are on my shelves, but that I hadn’t read yet:

Relations: An Anthology of African and Diaspora Voices, edited by Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond (who read for First Tuesdays back in September 2020): I was in graduate school in the mid-1980s when I was first introduced to the idea that English literature was not the monolith I had learned about as an undergraduate. I don’t remember the name of the course I took in my second semester, but, specifically to break down that monolith, the professor had assigned The Deptford Trilogy, by the Canadian novelist Robertson Davies and two or three of not-yet-Nobel-laureate Nadine Gordimer’s novels, though I don’t remember now which ones. That semester also taught me a lesson in just how stubborn hierarchies can be when you try to break them down. I decided to write one of my papers, maybe even the final one, on a novel that I really liked called The World Is Made of Glass, by the Australian writer Morris West, which I think I remember having taken down from my mother’s shelf before I left for school. I got a B on the paper, one reason for which, the professor told me when I asked to discuss it with him, was that I had chosen a book by a writer “no one had ever heard of.” (Take a look at West’s Wikipedia page. My professor might not have heard of him, but West was certainly no lightweight.) I say this by way of suggesting why Brew-Hammond’s anthology made such an impression on me. I knew something of the poetry being written in Africa through the New-Generation African Poets, but I had not paid close attention to the entirety of English-language literature being written in Africa and/or by people from Africa who are living in diaspora. (I know that using Africa as a catchall term is in some ways problematic because of all the erasures it contains, but the jacket copy lists twenty-seven countries as the writers’ places of origin and/or residence. I am conserving space.) Relations opens a wonderfully multiplicitous set of windows onto that diversity by including work from three genres, poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction, and through an admirable eclecticism of subject matter.

Soundtrack Of A Life: New and Selected Poems by Gil Fagiani, translated into Italian by Luigi Bonaffini: I met Gil only once, shortly before he was diagnosed with leukemia. We were in the process of scheduling a reading at First Tuesdays, which, sadly, never came about. His illness eventually killed him. I was glad, therefore, when Maria Lisella gifted me a copy of this book—which I read, obviously, in English, not the Italian translation. (Still, it was interesting to have the Italian on facing pages. Not that I read or speak Italian, but it was interesting once in a while—when I could follow a little bit—to compare the two versions, just to see how differently Italian handles, in syntax, line length, and so on what Gil was writing about.) The book is called Soundtrack of a Life, but, for me, the experience of reading it was more like paging through a photo album or a lifelong sequence of paintings. Fagiani’s poems capture moments in time—whether between the speaker and other people, the speaker and a place, or the speaker and himself—framing them the way a good artist does, so that meaning emerges as much from the unstated relationships between and among what the frame contains, as from what is explicitly stated (visible) on the surface. It’s a kind of poem I have a very hard time writing, and it was a real pleasure to spend a couple of days reading the work of someone who makes it appear truly effortless—which we all know is the sign of a true craftsperson. This is a book definitely worth picking up.

Two Articles

The Tyranny of the Female-Orgasm Industrial Complex, by Katharine Smyth: “The truth is that no one knows for sure why women come, and our descendants may well look back on such theories with as much derision as we do on the treatment of hysteria or the tie between climax and pregnancy. The female orgasm is a kind of Rorschach test—an abstraction upon which each new generation of doctors and scientists can project its worldview, almost always to the benefit of men and their assumptions about normally functioning female sexuality. But if you think the debate over why women have orgasms is complicated, try solving the mystery of why some women don’t have them.” Given Smyth’s assertion that she enjoys sex just fine even though she is anorgasmic, one way of phrasing the central question this piece asks is, “Why do we not trust women’s account of their own pleasure?” The lens she uses, though, about how the female orgasm has been weaponized against women/commodified to the point of there actually being a “female-orgasm industrial complex” made me think of “The Punctureproof Balloon,” the last chapter of David M. Friedman’s A Mind Of Its Own: A Cultural History of the Penis, which focuses on Viagra and what could reasonably be called the “erection industrial complex.” It’s a comparison worth exploring.

Why Are There So Few Conservative Professors?, by Steven M. Teles: “More conspicuously than at any time in living memory, elite higher education has found itself in the political crosshairs. While the Hamas attack on Israel — and the inept response of university leaders — lit the fire, the dry tinder for a political assault on our most prestigious universities has been sitting around for some time. Those who sense more than a whiff of political opportunism and anti-intellectualism in this assault are not mistaken. But the public’s impression that American higher education has grown increasingly closed-minded is undeniably correct. Indeed, concerns about the ideological drift of the university are no longer limited to conservatives, but now include some left-leaning faculty who worry that higher education has become, in the words of Gregory Conti, a political philosopher at Princeton, ‘sectarian.’ This mounting sectarianism manifests itself in various aspects of the university, including the scope of debate within and outside the classroom, the growth of campus administration, and the tenor of student life. For a professor like myself, the character of the professoriate is the most salient aspect of the change. And where conservative faculty are concerned, the facts are beyond dispute: Their numbers are low and continue to fall.” This very interesting essay from The Chronicle of Higher Education makes an argument worth wrestling with on why it’s important to reverse the left-leaning trajectory of higher education. My usual caveat applies: I don’t agree with everything Teles says, but he makes points about the value of an intellectual inclusivity that proactively includes conservative scholars that I think should not be ignored. An interesting companion piece, also published in The Chronicle is “Will Republicans Save the Humanities,” by Jenna Silber Storey and Benjamin Storey. Notably, both these essays see greater ideological inclusivity within the academy as a way of combatting what Teles calls the “political opportunism and anti-intellectualism” at the heart of the current attacks on higher ed. Both pieces, I think, downplay the profoundly reactionary goal of those attacks, but they are worth reading nonetheless.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

from Mira Calligraphiae Monumenta

The images below are all from the J. Paul Getty Museum.

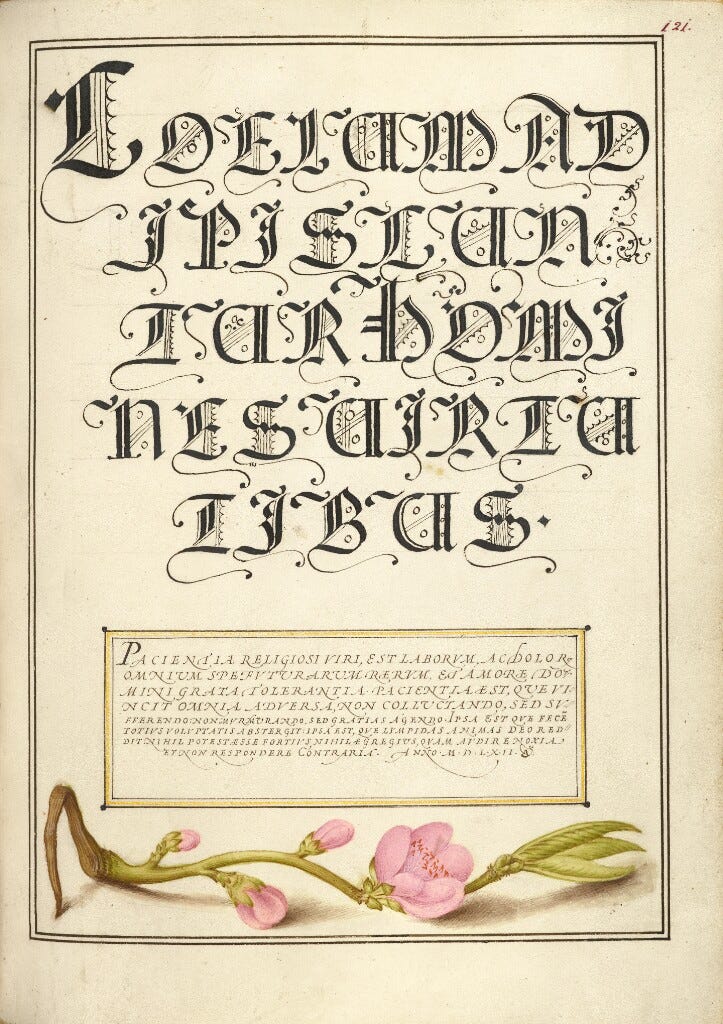

In the 1500s, as printing became the most common method of producing books, intellectuals increasingly valued the inventiveness of scribes and the aesthetic qualities of writing. From 1561 to 1562, Georg Bocskay, the Croatian-born court secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I, created this Model Book of Calligraphy in Vienna to demonstrate his technical mastery of the immense range of writing styles known to him.

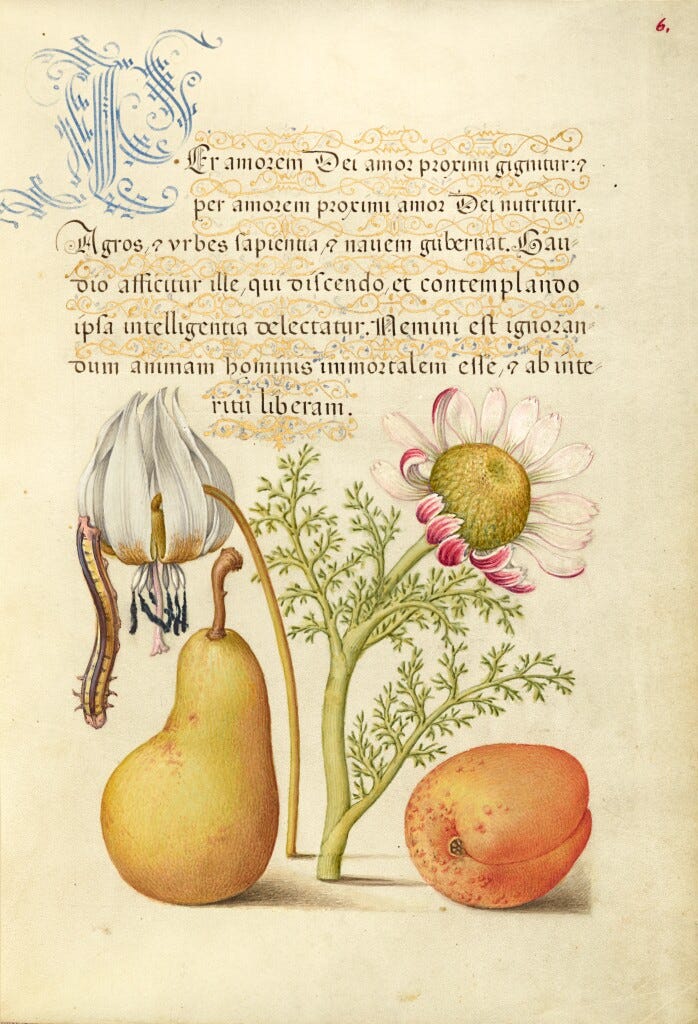

About thirty years later, Emperor Rudolph II, Ferdinand's grandson, commissioned Joris Hoefnagel to illuminate Bocskay's model book. Hoefnagel added fruit, flowers, and insects to nearly every page, composing them so as to enhance the unity and balance of the page's design. It was one of the most unusual collaborations between scribe and painter in the history of manuscript illumination.

Because of Hoefnagel's interest in painting objects of nature, his detailed images complement Rudolph II's celebrated Kunstkammer, a cabinet of curiosities that contained bones, shells, fossils, and other natural specimens. Hoefnagel's careful images of nature also influenced the development of Netherlandish still life painting.

In addition to his fruit and flower illuminations, Hoefnagel added to the Model Book a section on constructing the letters of the alphabet in upper- and lowercase.

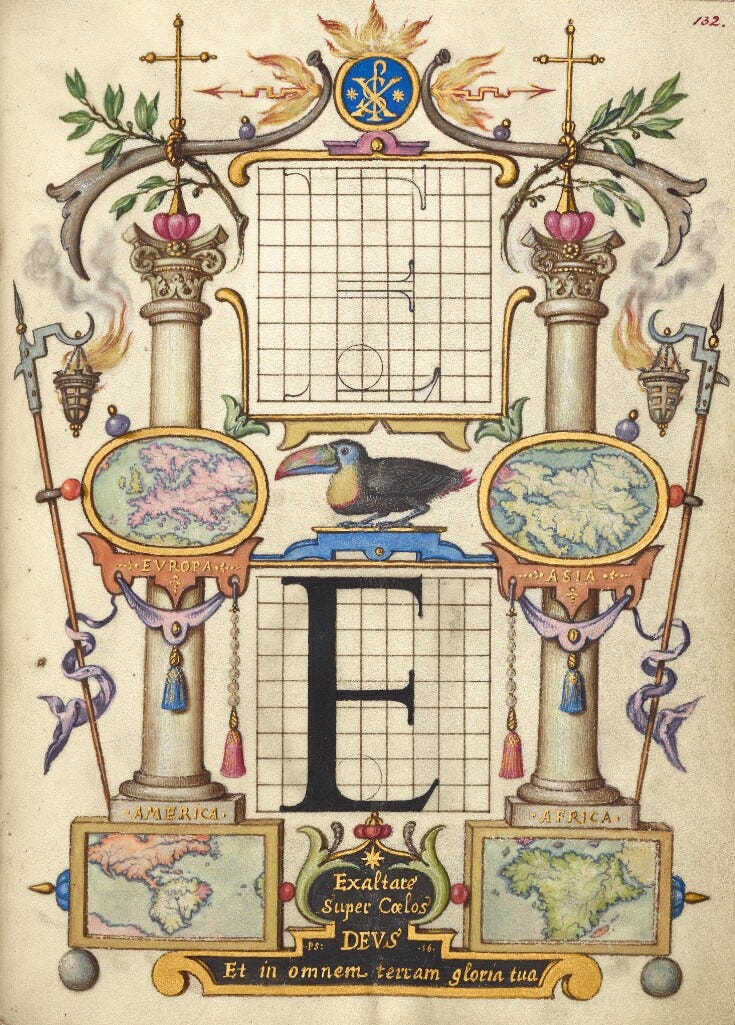

Guide for Constructing the Letter E

On two grids, Joris Hoefnagel demonstrated the proper form of a capital E , with the proportions of the letter determined by the relation of its parts to squares and arcs. About thirty years after Georg Bocskay finished his Model Book of Calligraphy, Hoefnagel added his Guide to the Construction of Letters to the manuscript. Hoefnagel's Guide uses diagrams to demonstrate how geometric principles might be applied to typographical design. The motifs surrounding these diagrams are charged with allegorical and symbolic meaning. At the top of the page, the XPS (Chi-Rho-Sigma) monogram for "Christus" in the azure medallion suggests the dominion of Christ over the world, represented by the maps of the continents on the sides. Echoing this idea, at the bottom of the page Hoefnagel included a verse from Psalm 56: Exaltare super caelos deus et in omnem terram gloria tua (Be exalted above the heavens, God, and your glory through all the earth). The two columns call to mind the so-called Pillars of Hercules, Habsburg imperial symbols since Emperor Charles V had used them in his emblem. The toucan probably does not have a specific symbolic meaning but interested Hoefnagel because of its rarity.

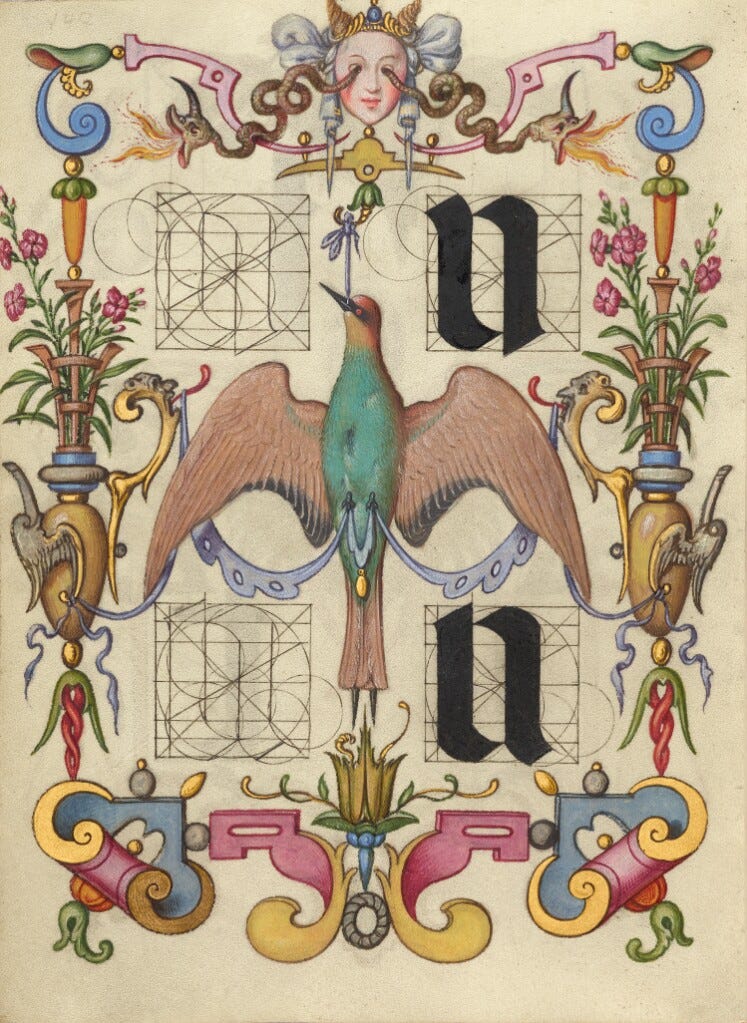

Guide for Constructing the Letters U and V

Almond in Flower

Caterpillar, Dog-Tooth Violet, Pear, and Apricot

Four Things To Listen To

Last Train To Clarksville Jeff Daniels Ben Daniels Band City Winery NYC 8/15/2018

I loved the Monkees when I was a kid, but I did not know until I found this video, that “Last Train to Clarkesville” was about a young man being shipped off to Vietnam.

Grace Potter & the Nocturnals with Heart - Paris & COY

Two rock and roll songs I really like.

4 Ballades, Op. 10: No. 1 in D Minor "Edward Ballade" - Andante

Fourplay "Bali Run" Live at Java Jazz Festival 2011

Four Things About Me

The first personal computer I owned was an IBM PCjr that my grandmother bought for me in 1985 when I went to graduate school. She insisted on buying an IBM machine, she said, because she owned stock in the company. In a precursor of things to come, though not until much, much later, the keyboard was wireless. I wrote my first graduate school papers on that machine, including the one on Morris West, which I mentioned above.

I don’t have that paper anymore, but I do have scanned copies of some of the other papers that I wrote on the PCjr. Here, for example, is a paragraph from a paper I called “The Problem of Form,” which I wrote for a course on modern poetry taught by a Professor Shires:

What is gained by thinking of prosody, the formal aspects of poetry, in the same way we think of the formal aspects of music? (It is important to remember that the comparison between music and poetry is not absolute; poetry cannot exploit the same kinds of vertical structures which music can. Rhyme comes close to being vertical, especially in a sonnet; but our experience of rhyme is still linear.) It is possible that we gain nothing; or that we lose more than we gain. Since music is another art form and carries with it its own vocabulary and its own set of conventions by which it must be experienced to be enjoyed by anybody, we may be making things more complicated for ourselves by trying to understand prosody in terms of music. However, certain confusions and problems do clear themselves up when we begin to think of prosody as music.

Reading this paragraph, which I wrote in the fall of 1984, I notice two things: first, the beginnings of how I have come to understand the role that form and craft play in my poetic and, second, a clear demonstration—though it took me a while to understand this explicitly—that my interest in studying literature had more to do with what it could teach me as a poet than with the pursuit of literary scholarship per se.

The next excerpt I am going to share with you, from a paper called “The Poet as Deviant” that I wrote on an electric typewriter for an undergraduate sociology class also shows that the core of my thinking about what it means to be a poet has not changed much from when I was in my twenties:

One of the things that is most important to a poet is recognition that his poetry is worth something. This recognition need not be from a large public; it could just as easily come from a few people who are very important in his or her life.

My MA in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) was, in practice and content, more of a degree in applied linguistics than in ESL pedagogy. This explains why one of the papers I wrote in pursuit of that degree was called “Political Language as Magical Speech.” In this paper, I compared what happens during a presidential State of the Union address to what happens when a shaman, or other community member understood to have magical powers, casts a spell. Ronald Reagan was president at the time. This, in part, is what I wrote:

Instead of a presidential report on the state of the union, we have a presidential invitation to enter with him into an optimistic belief that his words either are already true, or will be coming true sometime in the future. The State of the Union Address becomes, instead of a statement of fact, an expression of hope. And an expression of hope as an illocutionary act contracts for a very different set of behaviors than does a simple reporting of the way things are.

And, finally, an excerpt from another paper I wrote with the PCjr, a book review essay of Extraterritorial and After Babel, by George Steiner. Because I had studied linguistics as an undergraduate, I was very interested in Steiner’s critique of Chomskian linguistics, which is implicit in the first of the two following paragraphs. Now, though, I am drawn much more strongly to the idea embodied in the last sentence of the second paragraph: that translation, and literary translation in particular, and I would probably extend that to include literary creation in general, is an act of trust. Regardless of whether Steiner’s overall argument holds water—and, if I remember correctly, he came in for an awful lot of criticism (and ridicule)—given the state of our culture today, I think that idea is one we should hold to as strongly as we can:

Language is both a private and a public property. Each member of a language community shares the conventions and materials of their language; they also, however, bring a body of individual associations, a personal context, to the language. Each person speaks their own version, an idiolect, of their language. It is this idiolect which allows us to maintain a sense of self; without some way of separating ourselves from the community, we would be nameless. This functional view of language leads Steiner to the conclusion that the original linguistic impulse was inward, was a way for people to see themselves as unique. Interpersonal and interlingual communication came later in response to other economic and social needs.

People can lie, discuss the future and also what might have been. This quality of language, that it can be used to create “alternate worlds,” is, for Steiner, the main function of language. Through this “alternity” of language, this ability of language to transform the world, people need not face the actuality of death. Communication, translation, then, especially through literature, is a sharing of alternate world views, an act, for Steiner, of extreme trust.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion