Four Things To Read

One Book

Let Us Believe In the Beginning Of The Cold Season: Selected Poems of Forough Farrokhzad, translated by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr.: Forough Farrokhzad is one of Iran’s most important contemporary poets, both because of her vision—she dared to write unapologetically out of her own experience as a woman—and her craft, which broke new ground for Iranian verse in a whole lot of ways. Her life—the Wikipedia article I linked to above is a good place to start—was cut short by a car accident when she was thirty-two and she is one of those artists about whom it is impossible not to wonder what she would have accomplished had she not died so young. One of the things I admire about Elizabeth Gray’s translations is that they do not have the trace of romanticism/sentimentality that I detect in some of the other translations I have read. One thing I have learned about myself as a reader is that I tend to find connections between poets and writers that others do not necessarily see. I have heard Farrokhzad called Iran’s Sylvia Plath, and I understand why people would reach for that comparison, but the poet whose work came to my mind the most while I was reading this book was June Jordan. I have not yet thought very deeply about why, so I will offer here an intuitive leap that has primarily to do with craft. Jordan wrote somewhere—though I can’t find it now—about the concept of vertical rhythm, by which she means how the language moves itself down the page in a sort of contrapuntal relationship to the horizontal rhythm in each line. Gray’s translations, it seemed to me as I read, created precisely that kind of rhythm. I asked her about this, and this is what she wrote: “[Farrokhzad] uses syntax, especially parallel syntactical constructions that align with/ her line breaks or stanzas, to propel…the rhythm of the work forward…It’s often far more complex than mere anaphora.” I can’t speak to the original Persian, of course, but I think Gray’s translations capture that aspect of Farrokhzad’s poetry beautifully.

Three Articles

Boiling Macaroni in Space? You’ll Need a Weirdly Shaped Pot, by Andrew Chapman: “On Earth, gravity keeps water at the bottom of a pot. In microgravity, however, keeping water contained within the pot so it doesn’t float away is a big issue. But water molecules are also attracted to each other, and to any surface they touch; when water is weightless, capillary action and surface tension can have a much larger influence on keeping water in one area within the pot.” An interesting article about a potential solution to a problem that will have to be solved if we want to be able “to think about a life in space that is as much about thriving…as it is about surviving.”

Kamala Harris and the Threat of a Woman’s Laugh, by Sophie Gilbert: “In insisting that Harris’s laugh is somehow a sign of psychological depravity or narcotic-induced lack of inhibitions, conservatives are doing their best to couple Harris in people’s subconscious with a specific reaction: disgust.” A quick but interesting read on how the politics of disgust has been, and continues to be, deployed by conservatives against women who seek political power. Nor is this phenomenon restricted to the United States and west. The Taliban beat women who were seen laughing in public and, as Gilbert points out, as recently as 2014, a former Turkish deputy prime minister suggested that women not laugh in public, since their laughter could be read as a sign of “moral corruption.”

New York’s First Black Librarians Changed the Way We Read, by Jennifer Schuessler: “For Black librarians of the period, librarianship wasn’t just about hosting writers or connecting books with patrons. It was also about creating an intellectual infrastructure that made Black materials visible — and findable — in the first place.” This article not only makes visible the first Black women librarians and the role they played in building “communities of readers” for Black writers and scholars; it also shows how these women transformed library cataloging systems in ways that had profound political implications that went far beyond issues of race. Shuessler’s piece is especially important today when libraries are increasingly under attack by the right.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

The Plate Mansion by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849)

A traditional Japanese Ukyio-e style illustration of traditional Japanese folklore ghost, Okiku. Original from Library of Congress.

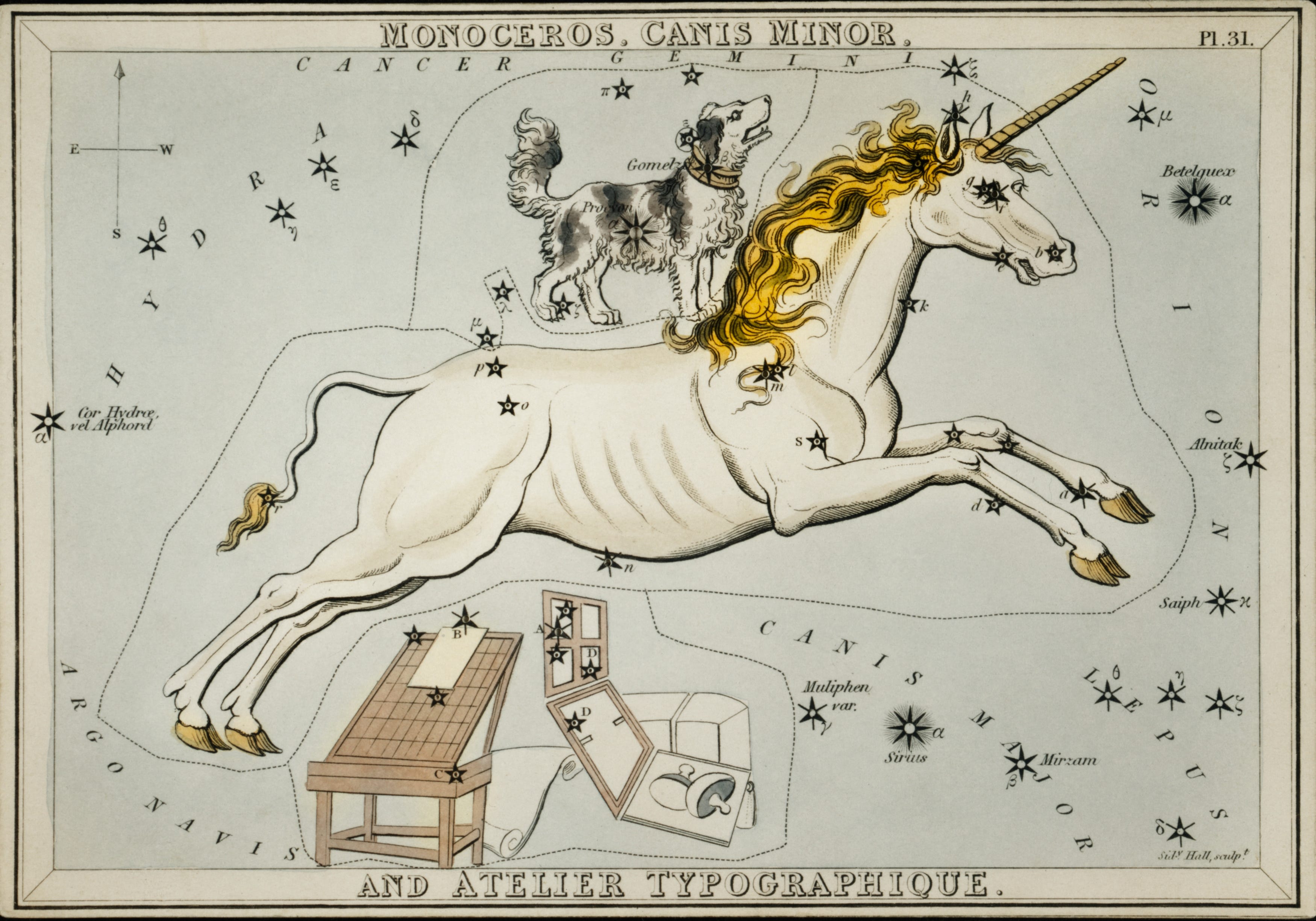

Astronomical chart illustration of the Monoceros, Canis Minor and the Atelier Typographique.

By Sidney Hall (1831) Original from Library of Congress.

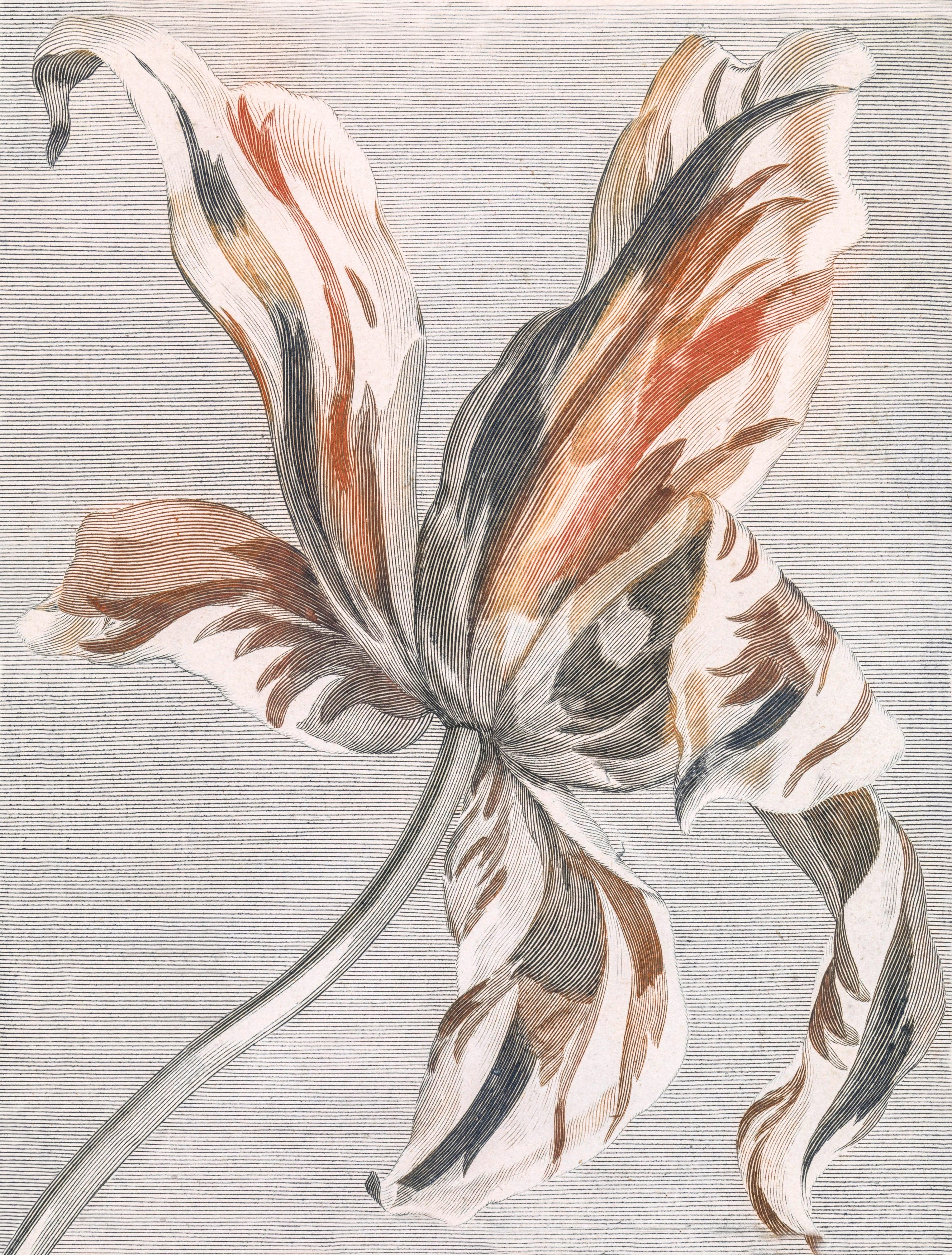

Tulip, by Johan Teyler (1648-1709).

Original from The Rijksmuseum.

Magnolia Branch with Four Flowers (ca. 1910-1925).

Original from the Rijksmuseum.

Four Things To Listen To

Boat to Nowhere - Anoushka Shankar

Glen Gould - Ombres (Shadows)

A composition by Barbara Pentland

The Path To The Bridge

The epigraph to T’shuvah is the lyric to a song, Kol Ha’Olam Kulo, that I learned when I was in high school. (The link will take you to a version by Ofra Haza.) The words—כל העולם כולו גשר צר מאוד, והעיקר - לא לפחד כלל (Kol ha’olam kulo gesher tzar me’od, veha’ikar lo le’fached klal)—which were adapted by Baruch Chait from a saying by Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, mean, roughly, “All the world is a very narrow bridge, and the most important thing is not to be overwhelmed by fear.” It’s a song I’ve been playing on the piano for a long time and it came to mean a lot to me while I was writing T’shuvah. I recorded this improvisation on my iPhone. I’ve called it “The Path To The Bridge” because the melody to the song itself does not appear until the very end.

The Bridge Is A Blues

This is also an improvisation on Kol Ha’olam Kulo, but played on a different piano and in a very different style.

Four Things About Me

I expected to encounter profound cultural differences when I went to Seoul, South Korea to teach English for the 1986–87 academic year. One thing I did not anticipate at all, however—and this shows you how deep ethnocentric thinking runs—was that I would also experience what it was like to be a racial minority. I don’t remember how long I’d been in the country before it hit me that I did not see my face reflected back at me pretty much anywhere in Korean society—not in the people I saw on the street or rode the subway with; not in the faces and bodies I saw in magazines and on TV (though the Armed Forces Korea Network (AFKN) and the western movies that played in some theaters were obvious exceptions); not in the faces of the men and women who were part of my life, as students, friends, and/or lovers—but I do remember very clearly looking at myself in the mirror after a long night of being out with my friends and realizing that I’d forgotten what I looked like, that my western features seemed strange to me, “off” somehow.

It’s not that I didn’t know what it was like to be a minority. As a Jew who’d experienced antisemitism, violent and otherwise for a good portion of my life, I knew that all too well. I had never experienced, however, what it was like to be defined as Other based solely on the inescapable facts of my physical appearance. Not that this experience was at all equivalent to what people of color experience here in the United States—I did not, for example, have to worry about racist violence of any sort—but I did learn what it was like to be feared and fetishized because of my appearance. More than once when I was riding the train, a baby started crying after taking one look at my face; and I also had the experience of older women coming up to me and, without asking permission, stroking what was then the thick black hair on my arms. Once, when I was out dancing with some friends and a woman started flirting with me, one of my friends, Jun Won, told me to be careful, that she was probably only interested in “riding the white horse,” a bucket-list kind of idiom that Korean men used back then—I don’t know if it is still current—for having sex with a white woman, but which, he explained, could apply to Korean women as well. The woman’s friends pulled her away because they’d decided to go to another club, so I have not idea if Jun Won was right.

The only thing I remember about the first poem I wrote in which I explicitly confronted my experience as a survivor childhood sexual violence are the last two lines—Your image fades./You cannot know.—but I do not remember to whom they were addressed or the context in which the speaker of the poem said them. I wrote the poem in 1985, not too long after I dropped out of Syracuse University’s MA in Creative Writing. I sent it to Philip Booth, who’d led our second-semester workshop. I don’t know if he knew how far ahead of its time his response was, but reading it even all these years later can still bring tears to my eyes:

That’s in all ways an important poem for you to have written, yes. And it’s a very considerable poem by any standard. What it means to have written it, to have found such terms for such experience, I don’t want to presume to guess. The important thing now is that you have done it, that is no longer entirely inside you but out there on the page, an act of courage and an event in its own right, a way of exploring in order to come to terms, to arrive in order—again—to begin.

The other thing I remember is not about the poem itself, but about how the editor of a journal to which I submitted it responded. I don’t recall the exact wording, but he’d written it on the back his rejection slip, which in my memory was blue. It went something like this, “You can call me whatever kind of heartless monster you want, but don’t ever submit another poem to this journal again.” While I’m sure I listened to him in the years immediately following that response, since I don’t remember the name of the journal and have no idea if it’s still in existence, I have no way of knowing if a time came when I did submit there again.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

A poet and essayist, I write about gender and sexuality, Jewish identity and culture, writing and translation. My goal? To make connections that matter. I also help other writers do the same.