Four Things To Read

One Book

The Great Dismissal: Memoir of the Cultural Demolition Derby, 2015–22, by Henry Sussman: ”[I]t is more urgent than ever for us to explore and articulate the commonalities of the professoriate and other university workers with journalists, librarians, school directors, dramaturges, and managers, editors, therapists, and clinicians of various stripes, and even attorneys (in their capacity as ‘counselors’). What this rather amorphous conglomerate of vocations holds in common is the dissemination of literacy—the act of inculcating others into the articulate, differentiating, and modulating capabilities within the panoply of language systems and social codes. The combined effect of these varied roles and functions is nothing other than the distribution of empowerment—outfitting neighbors to full cultural enfranchisement.” The central, crucial importance of literacy in all its various guises as the only foundation from which an adequate response might be launched against the right-wing onslaught against what it means to be literate, as Sussman defines it here, is the core theme of this book. The book itself is not easy reading, nor is it intended to be. Sussman gathers into essays, along with a few poems, a broad enough range of cultural analysis that one reading is certainly not enough fully to grasp what he’s talking about. My own experience of one reading is this: At the beginning of the book, Sussman elucidates that value of the kind of meticulously close reading practiced by Derrida—who was Sussman’s teacher—and other cultural theorists and then goes on to illustrate how this way of reading plays out in four books that he then uses throughout these essays as touchstones not only of analysis, but also of the potential for change: Dark Money, by Jane Mayer; The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, by Shoshana Zuboff; Foxocracy: Inside the Network’s Playbook of Tribal Warfare, by Tobin Smith; and The Cruelty Is The Point, by Adam Serwer. Sussman draws from many more sources than these—journalists, columnists, sociologists, theorists—but, at least in my first reading, the issues raised by these four books (money, technology, the media, the United States’ history of oppression, and how the right has marshaled them all to its cause(s)) form the infrastructure of his argument. The Great Dismissal is well-worth reading.

Three Articles

“At Michigan, Activists Take Over and Shut Down Student Government,” by Halina Bennet: "At the University of Michigan, many student activities are usually funded or subsidized by the Central Student Government, known as C.S.G., an elected undergraduate and graduate council that decides how to dole out roughly $1.3 million annually to about 400 groups. But last spring, pro-Palestinian activists, running under the Shut It Down party, won control over the student government. They immediately moved to withhold funding for all activities, until the university committed to divest from companies that profit from Israel’s war in Gaza.” I am fascinated by Shut It Down’s strategy, which one the one hand feels not so different in principle from workers seizing the means of production, while at the same time being reminiscent of the way the right has increased its power and influence by running in and winning local elections. I know there are those who will argue that what Shut It Down did crosses a line, though it’s not clear to me what that line is. It’s not just that I am personally sympathetic to the idea that people should not be able to turn a blind eye not only to what Israel is doing in Gaza, but also to the ways the institutions in which we are implicated support Israel’s actions, tacitly or otherwise. Whether you agree that what Israel is doing in Gaza is technically a genocide or not—and I am not insensitive to the political complexities embedded in the use of that term—to argue that Israel’s actions do not call for some kind of deviation from business as usual is ultimately to argue, on some level, for the normalization of those actions. I also want to add did find the group’s relative silence, as reported in the article, concerning, though, to be fair, the new semester has only just started. It will be interesting to see if there is any follow-up coverage.

“The Fallacy of the Literary Citizen,” an interview with Alina Stefanescu published in The Only Poems Newsletter: "As a concept, literary citizenship acknowledges the duties of citizenship (however those are constructed or interpreted) vis a vis the Republic of Letters, while downplaying the underlying inequality between various passports and citizenship regimes. Obviously, some literary citizens are freer than others—but the concept wallpapers over such distinctions…Let’s imagine a concept of literary community that refuses the hierarchical power dynamics of states. A concept that reconfigures solidarities in defiance of nation-state citizenship rather than accepting that vision for the future.” When I teach creative writing, I always include two or three “literary citizenship” assignments which ask students to participate in literary activities of one sort or another, including but not limited to going to a reading, reading at an open mic, submitting work to the student literary magazine, or becoming involved in producing the magazine. If I remember correctly, I chose to use the term “literary citizenship” to make the assignments congruent with a similar requirement creative majors have to fulfill in order to receive their degree. For me, the term is connected both to the notion that one purpose of public education—and I teach at a public institution—is to prepare students for meaningful, critical, substantive citizenship and to the fact that public eduction has been one of the most powerful democratizing forces in the history of this country. (One reason it is now under attack from the right.) In this interview, Stefanescu troubles that notion in important ways by making visible how the term citizenshipvalidates, in both its denotations and connotations, hierarchies of worth and systems of oppression and exclusion. Ultimately, she raises the question of how the notion of literary citizenship shapes what we understand the cultural role of literature to be and whether or not that is in fact the role we want our work to play. Her argument is well worth taking the time to think about.

“The Internet Is Not Forever: 38% of Web Pages From 2013 No Longer Exist,” by Rob Pegoraro: “A new study on the state of link rot suggests that a floppy disk might have better odds of surviving the next decade with its information intact than a web page published today. The Pew Research Center finds that 38% of the pages extant in 2013 were no longer accessible in October 2023 and that a quarter of the pages that were online at some point over that period have now vanished.” Pegoraro points to this study and the phenomenon it captures should concern all of us as the world becomes more and more embedded and invested in, as well as dependent on, digital media. I don’t have much to say about this other than that I think it’s important to be informed about phenomenon, even though the overwhelming majority of us are in no position to do much of anything about it.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

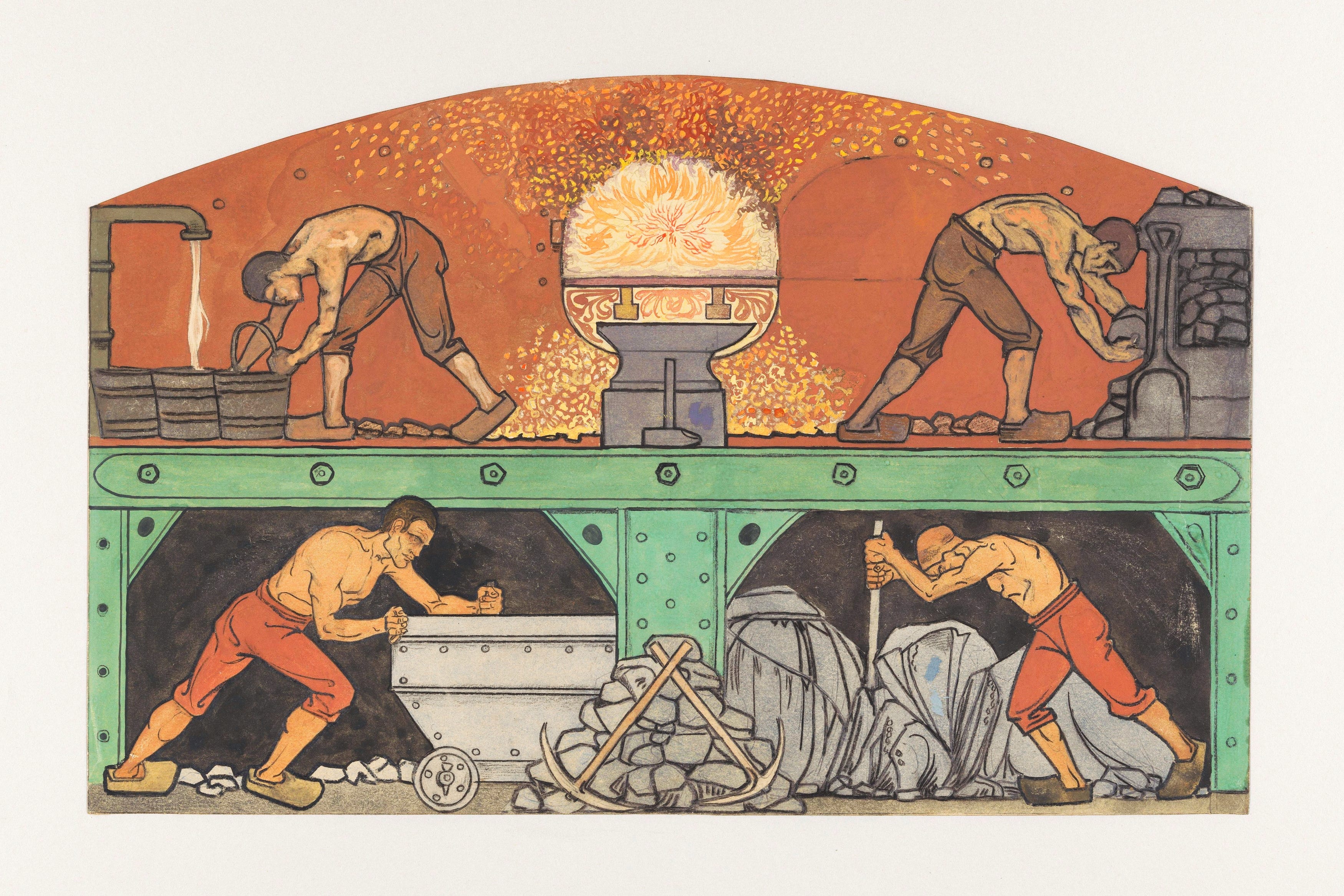

Richard Roland Holst (1868-19368) was a man of many talents, an author, sculptor, etcher, glass painter, professor, illustrator, lithographer, furniture designer, painter, draftsman, muralist and more. Born into a wealthy Dutch family, he still had an understanding for the life of the working class. A trend among young artists in the Symbolist movement was to convey social messages and not only focus on monetizing. Holst used his social commitment in his art as well as politically in the Social Democratic Workers’ Party. As a professor at Rijksakademie he promoted his artisanal and ethical ideology to his students. He believed that art had an important role to play in society as it had the ability to reach the whole population.

A Farmer Standing Near A Hay-Stack (1889)

Original from the Rijksmuseum. Digitally enhanced by rawpixel.

Head Of The Blindfolded Justitia

Designed for the marble decoration in the Supreme Court in The Hague (1868–1938). Original from the Rijksmuseum.

Horse Head (1881)

Original from the Rijksmuseum.

The Industry (1878-1938)

Original from the Rijksmuseum.

Four Things To Listen To

Jackson, Johnny Cash & June Carter Cash

Manssa Cise, Habib Koité

New Old Age, Peter Erskine

Oxygène, Part 2, Jean Michel Jarre

Four Things About Me

I’ve only been in one fistfight, ever. I was in third grade. We’d just moved into the neighborhood and one of my classmates asked me during recess what my religion was. I told him. The next day, when we were choosing up sides for a recess game of dodgeball, he told me I couldn’t play because his parents told him he wasn’t allowed to play with Jews. I don’t know if the fight I’m telling you about happened then or if it happened some time after that, but I remember being shoved into the center of a schoolyard circle of boys. “He’s a Jew! Punch him in the face!” I heard someone call out. I tried to break out of the circle, but they pushed me back into the center where I had no choice but to face off not with the boy I just told you about, but with the toughest boy in the class. (Both of them happened to be named John.) I don’t remember if he swung first or if I did, but I know I connected with his jaw and that blood started to trickle down his chin. The other boys saw it as well and, all of us suddenly horrified, we quickly dispersed. I have no recollection of what happened next, only that the blood turned out to be from a scab on his chin that I broke and not from any serious damage that I’d done to the boy’s face. The experience, though, frightened me enough that I have managed, even in situations where it might have been justified—and when I was younger and still living in that neighborhood there were more than a few of those—I have managed never to hit someone like that again.

I remember when I started not to believe in a god. I was in my late teens or early twenties, sitting in shul on either Rosh Hashanah or Yom Kippur and listening to the rabbi’s sermon. He was talking about the “Al Cheit,” the communally recited confessional prayer, each line of which is addressed to God and begins “For the sin we have committed before You.” I don’t remember exactly what he said, but he connected it to the lines from the Avinu Malkeinu that are recited between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, in which the congregation, again communally, asks God to: “[I]nscribe us in the book of good life, …in the book of redemption and deliverance, …in the book of livelihood and sustenance, …in the book of merits, …in the book of pardon and forgiveness.” I suddenly had this image of God as a bookkeeper, complete with a green tinted visor, tallying up everyone’s sins and good deeds on a balance sheet. The image reminded me, frankly, of what God might look like in a Monty Python skit, if the members of Month Python had been Jewish. No matter how hard I tried—and I did try—I could not get that metaphor out of my head, which made it increasingly difficult to take the idea of God–of a god, of any god–very seriously.

I was suspended from school in eleventh grade for cutting class with all the girls in my grade. The boys in my class–this was when I was in yeshiva–were scheduled to take a class trip to a yeshiva in Lakewood, New Jersey. I don’t remember which one. For some reason that I also don’t remember, I was not able to go on the trip with them. Since our morning classes, which were religious studies, were segregated by gender, that meant I spent the morning by myself with nothing to do but shoot baskets and fiddle around on the piano that was on the stage in the room that did triple duty as a gym, a dining hall, and an auditorium. When it came time for the afternoon classes, the girls and I decided not to go, since more than half the class wasn’t there. We got caught because the boys’ bus broke down after stopping, I think in Brooklyn, so they could get a blessing from Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. The bus got fixed in time for them to go to first period math. The girls and I, of course, were conspicuous by our absence. We were suspended and told we could not go back to class until our parents came in to speak with the principal of secular studies. My mother couldn’t do that because she worked, so she had to make an early morning appointment with the dean of the school, according to whom the bigger problem wasn’t that I had cut classes, but that I had been alone with all the girls in the class without any supervision. He couldn’t bring himself even to suggest to my mother that I had done anything sexually inappropriate, though, so all he said was, “I want you to know that your son is a real mensch. He made a mistake. I am sure he will never do that again.” That was it. I walked my mother out of the building to her car and, as soon as we got outside, she started laughing. “What were you actually suspended for?”

I had a serious girlfriend when I was in my twenties. Early on in our relationship, she asked me what I thought our home should be like if we ever decided to get married. It told her that, assuming we could afford it, we should have a place with three bedrooms, one that we shared and two more so we could each have our own private space, in case we wanted to sleep alone or if we wanted to work late into the night—at the time, she thought she would be an artist and I knew I was going to be a writer—and we didn’t want to disturb the other’s sleep by climbing into bed with them. She was horrified. “That is the most unromantic thing I have ever heard,” she said. A few years later, though, when the possibility of us living together and maybe getting married was becoming more and more real, she brought the subject up again. “The more I think about it now,” she said, “the more I like your idea of us having separate rooms in addition to the one we share.” I don’t remember if she told me what changed her mind, but it didn’t really matter in the end. We broke up not too long after that.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

A poet and essayist, I write about gender and sexuality, Jewish identity and culture, writing and translation. My goal? To make connections that matter. I also help other writers do the same.