.

Four Things To Read

One Book

Doors tae Naewye, by Christie Williamson: Written primarily in Shetlandic, a dialect of Scots that is spoken in Shetland, an archipelago off Scotland’s north coast, this is Williamson’s second book. (The first is Oo an Feddirs, which also contains a fair number of poems in Shetlandic.) Each Shetlandic poem is accompanied by a translation, printed in smaller, italicized text with slashes and double slashes to indicate line and stanza breaks. I wish the publisher had been able to print the translations on facing pages, though, because they are beautiful in their own right and being able to read them typeset as poems would help to give the reader a better sense of the syntactic, rhythmic, and sonic movements in the original. Williamson uses line breaks to great effect in this regard, for example, and the music he achieves melds the personal and the political into poems that, as often as not, command several readings. I met Christie Williamson before the pandemic shutdown, when he came to the States to be part of the annual poetry dinner held at the now defunct Roger Smith Hotel. I also brought him out to Nassau Community College, where I teach, to give a reading for our Creative Writing Program. We exchanged books afterwards, but I did not get a copy of Doors tae Naewye until my wife and I made a trip to Scotland over the summer and I was lucky enough to get to see Christie while were in Glasgow, before we made out way down to London for a family wedding. I was happy and more than a little bit humbled to find the title of my book incorporated into the first poem in this one:

Dawn

In LaGuardia I read

The Silence Of Men.

My case is checked,

devices safe and close

to hand. I wait.

I see a guy—be could be anything

from forty to seventy-five. Dreads

hang loose around his neck.

This guy has lived.

I see the torn rags

that just keep his feet off the ground,

taking step after step, always

forward—to what?

I think of the heavy shoes

I paid those bastards at American

to carry. I want to dig them out, say

“Here you go buddy—walk a mile.”

Like all these dreams it slips

away as quickly as it came.

I sit, with ten kilos of books

and not one word to say.

§§§

Three Articles

Octopuses are now punching fish in the face. This video shows exactly why. by Beki Hooper:

Individuals in the group do not share what they kill, but each group member increases the likelihood of making a kill by working together. Teamwork is therefore beneficial for everyone. That is, until individuals try to exploit the group by catching prey without helping to find it or flush it. The octopuses do not put up with this behaviour, though. They punish the cheaters by punching them with their tentacles.

Hooper reports on a study, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution of underwater multi-species hunting groups in which Octopus cyanea, a species that is normally solitary, works with different kinds of fish to find prey. The roles within the group are pretty well defined. The fish decide in which direction the group should search for prey, while the octopus flushes the prey out of its hiding spot, but when “individuals try to exploit the group by catching prey without helping to find it or flush it,” the octopus assume the role of enforcer and punches the offending member. There are two videos in the article, one of an octopus punching misbehaving fish and one of the octopus and the fish hunting together. It’s in some ways a scientific version of the videos you see on social media of different species of animals befriending and cooperating with each other, but, as Hooper points out, the study raises some really interesting questions, among them the nature of octopus social intelligence and how the members of the hunting party communicate with each other, which scientists theorize might have to do with “octopus skin patterns.”

§§§

Black Hole, by Robert Jensen:

Some years are a complete blank, others are fragmented and sketchy at best. I have, literally, no recollection of the first six years of my life. From age six to eleven, it’s a jumble of disconnected fragments. Starting at twelve, I can start to accumulate enough fragments to piece together a tentative narrative, albeit with big gaps. And there’s one really big gap when I was fifteen, my sophomore year in high school; that year is completely blank. Starting with the year I was sixteen, I have something that seems to approximate the kind of memory most people taken for granted.

Jensen, whose work is worth checking out, perhaps especially his feminist writing, takes on in this essay—a guest post on Julie Bindel’s Substack—the way in which the abuse he suffered as a child has impacted his memory. For me, the most poignant part is when he considers whether it is better to know or not the things that he has blocked from memory and how comparing what it means not to know/remember to the situations of people who do know/remember can lead to some pretty counterintuitive feelings.

§§§

She Exposed a Prestigious Medical Journal’s Silence on the Holocaust. Now She’s Asking About Gaza, by Jonah Valdez:

“Is the silence of [The New England Journal Of Medicine] regarding the pulverization of the health care system in Gaza, and Israel’s relentless attack on health care workers and the creation of a public health and humanitarian disaster and the weaponization of starvation similar or different to its silence during the Holocaust?” Abi-Rached said toward the end of her talk, joining the symposium virtually from Paris. “What explains the erasure of the predicament of Palestinians in the pages of the journal? What do we mean by the political determinants of health if we precisely ignore the plight, the health, and well-being of marginalized and vulnerable populations?”

Comparisons of Israel’s war in Gaza to the Holocaust are often facile or straightforwardly (and even antisemtically) manipulative, not because what Israel is doing is not genocidal, but because singling out the Nazi’s campaign against the Jews as the point of comparison, when there are other genocides which would serve equally well, implicates all Jews worldwide in a collective responsibility and accountability for what the Israeli government is doing. The comparison Jonah Valdez reports on here, however, is well worth thinking about, since it is ultimately about institutional response to genocide—in this case on the part one of the longest-running and most prestigious medical publications in the country—regardless of who the perpetrators and victims happen to be. Joelle M. Abi-Rached and Allan M. Brandt published an article called “Nazism and the Journal” in the March 2024 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine.” Part of “an invited series by independent historians, focused on biases and injustice that the Journal has historically helped to perpetuate,” Abi-Rached and Brandt’s piece focused on the Journal’s choice to remain silent about the role played by the Nazi health care system in furthering the Nazi’s genocidal program. The authors were invited to speak about their findings at a symposium last week, and it was during that symposium that Abi-Rached asked the questions I quoted above.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

All images are from the National Gallery of Art and are in the public domain.

Portrait of a Woman - 2nd Century Egypt

§§§

Portrait of A Lady

Rogier van der Weyden, Netherlandish, 1399/1400 - 1464

§§§

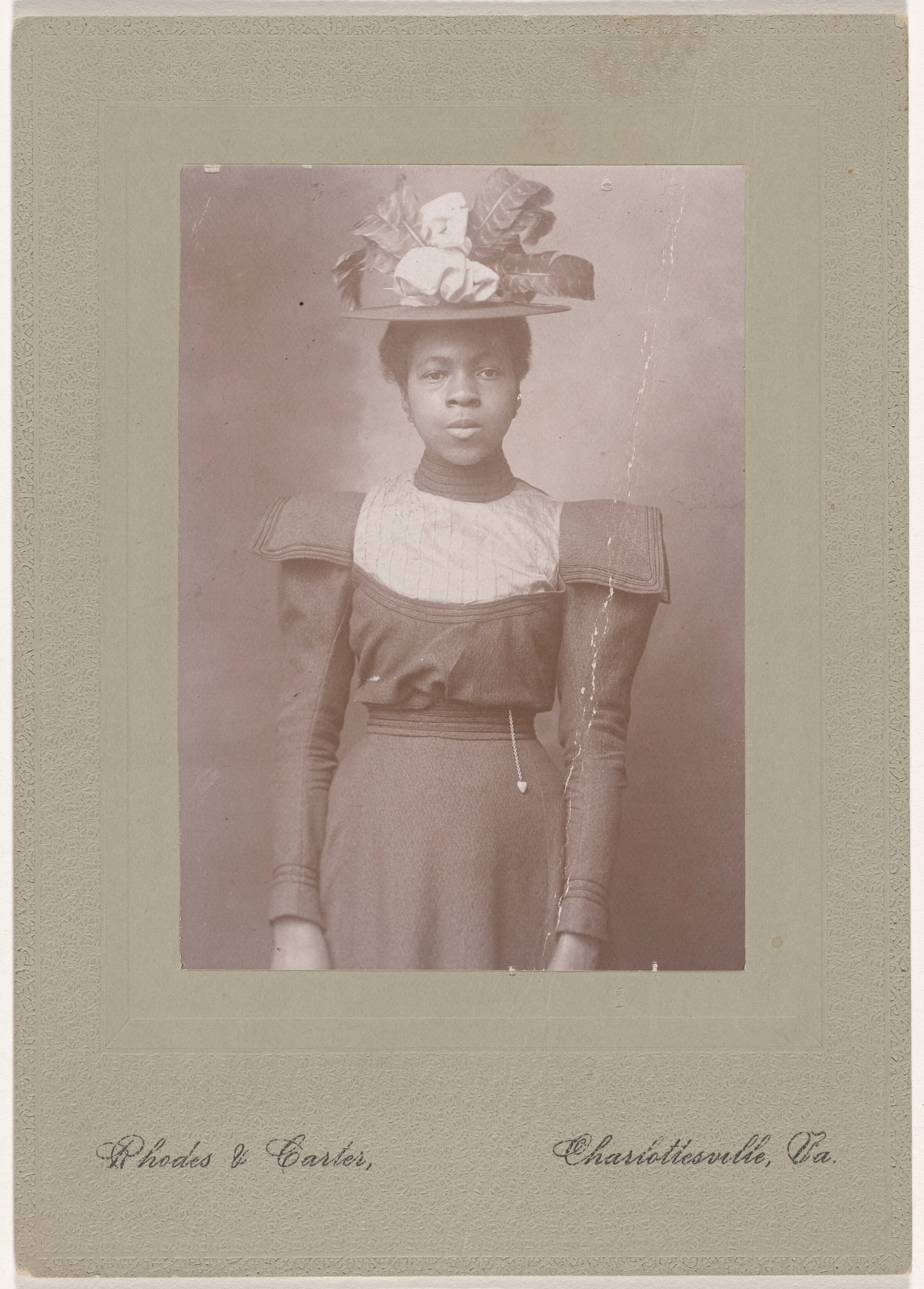

Portrait of a Woman

Rhodes & Carter (artist) American, 1890s - 1910s

§§§

Mr. and Mrs.

William J. Rensler (artist) American, 1891 - 1946

Four Things To Listen To

Giora Feidman - The King of Klezmer - Sholem Alekhem, Rov Feidman

§§§

Blood Orange - Sutphin Boulevard

§§§

Bela Fleck & The Flecktones - Life in Eleven

§§§

Baiuca - Morriña

Four Things About Me

When I returned in 1989 from my year of teaching in South Korea, I stayed at my grandmother’s house while I looked for a job and a place to live. A friend from Seoul, a Korean woman, came to stay with me there for a couple of days before going to the university where she would be pursuing a PhD in English literature. One evening, I said I would cook dinner. My friend was incredulous. She didn’t think I would be able to do it. At the time–I have no idea what it’s like now–cooking in Korea was absolutely “women’s work” and so Korean men generally didn’t do it. I remember laughing as my friend stood in the kitchen absolutely engrossed by the fact not only that I knew where everything was, but also that I knew how to peel and slice and onion, how to mince garlic, and how to do whatever else it was that the meal required. (I don’t remember what I cooked.) Eventually, satisfied that I really did know what I was doing, she went into the living room to read until the meal was ready. The last thing I prepared, which she didn’t see me doing, was the rice, and, like I had learned from my mother and grandmother, I cooked Minute Rice. (Or maybe it was Uncle Ben’s. In any event, it was one of the brands of instant rice.) When I put the rice down in front of my friend, she spooned a small portion onto her plate, poked at it with her fork, put some in her mouth, and frowned. “This isn’t rice,” she said, the disappointment dripping from her voice. At first, I didn’t understand what she meant, so I brought the box from the kitchen to prove to her that it was indeed rice, though I could not imagine what else she might have thought that it was. What I realized from the ensuing conversation was that, despite my having eaten Korean rice for a year, I’d never really thought about how different it was from the rice I was used to having at home; and it was very different. It had a different taste, a different texture, a different body. Nor had I thought much at all about why one of the questions Koreans ask when they want to know if you’ve eaten a meal translates literally as, “Have you eaten rice?” The way I understood my friend’s explanation was that it’s not so much that rice is the meal as much as, without rice, there is no meal, and instant rice just doesn’t pass muster in such a cultural context.

§§§

When I was a kid—I don’t remember how young I was—my mother had a friend named Rose who lived on our building. Our apartment was on the ground level, and Rose’s was on the top floor, I think. Rose was also a single mother. She had two kids, a daughter Patti, with whom I became good friends, and a son, whose name I’ve forgotten. Rose had a boyfriend, whose name was Joe. I remember once Joe took us—me and my brother, Patti and her brother—to Jones Beach at night, something I’d never done before. I don’t if I am making this up, but I have a memory of us talking off our shoes and socks, rolling up our pants, and walking ankle deep into the water. What I know for sure is that we had fun. I have no recollection of who told me—probably it was my mother—but one day they found Rose dead in her closet, stabbed sixteen times in the chest with a serrated knife. Everyone was sure Joe did it, but he had an alibi, and so if he did do it, or if he paid someone else to do it, he got away with it. Patti and her brother moved away, of course, and I saw Patti only once more, when for some reason—I don’t know how long afterwards—she showed up in the development where we lived. I had no idea how to talk to her, and so we did not reconnect at all, and I never saw her again. My other enduring memory of what happened after Rose was murdered is of another woman in our building standing just inside our front door, holding a basket filled with laundry. She’d come in to hide from Joe, who I guess came back to get his things from the apartment and whom she was absolutely sure was the killer. Now I wonder, based on what I remember of her behavior, if she’d actually seen something and had good reason to be afraid that Joe would have come after her if given the chance.

§§§

When I was young, I collected coins like my grandfather and stamps like my stepfather. Neither one stuck as a hobby. There was, though, a coin and stamp dealer named Woody who had a store in our neighborhood. I loved to go there and look at what he had in the display cases, fantasizing about getting for my collection some of the truly valuable coins and/or stamps that he had there. I also really liked listening to him talk about the different ways he had found—that he implied I might be able to find as well—those rare “specimens that were still out in the wild,” as he described it. It was because of those discussions, as much as anything I learned from my grandfather, that I developed the habit of checking every coin I lay my hands on for its date and its condition. I did that for years, even after I stopped collecting, occasionally finding a Buffalo Nickel or a Mercury Dime, though never one that was worth much more than their five or ten cent face value. I have not seen either of those in a very, very long time, but I also don’t really look anymore.

§§§

I was very interested in fortune telling when I was in my early teens. I remember having a book that had instructions on how to read palms, tea leaves, and tarot cards, and I think it may have had a section on the I Ching. I don’t remember what I actually believed about these methods of divining the future, but I found them fascinating. I don’t remember when or why my interest fell away, but when I think about them now, I try to understand them as providing a framework for and giving structure to self-reflection; and when I think about it like that, I’m not so sure they are, at least for the people who take them seriously, either more or less meaningful than any of the other systems humans have designed to help themselves live decent lives.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

A poet and essayist, I write about gender and sexuality, Jewish identity and culture, writing and translation. My goal? To make connections that matter. I also help other writers do the same.