Four Things To Read

Late to the House of Words: Selected Poems by Gemma Gorga, translated by Sharon Dolin:

A reader will note a consistent interplay in [Gorga’s] work between the literal and the figurative, where everything is and is not itself. Thus, the “murky color” of the pomegranate’s stain on “our fingers” becomes the “open color of memory.” In her poem “Amusement Park,” the poet has a date with sadness, and while she conjures up the image of a ride on a Ferris wheel, she soon transforms it into an existential state: “How long have I been spinning round on this Ferris wheel,/now close to the world, now farther away?”

That’s from Dolin’s introduction, and it captures what was, for me, the most salient aspect of reading this book: the element of play that kept me interested from start to finish. And not just interested. It’s been a long time since I read a book of poems about which I could say, simply, that I enjoyed it at the level of sensual pleasure–and I include in this pleasure that which accompanies the intellectual and emotional leaps the reader has to make between the literal and figurative. I know Dolin’s work from Burn and Dodge, where she shows herself to be a meticulous craftsperson, a facility you can see at work in the sparse and carefully shaped lines of this translation. That level of care and attention to detail is what allows the play—of language, of ideas, of metaphor—at work in the center of Gorga’s poetry to be, simply, seriously, deeply, the pleasure that it is. The poems definitely deserve more than one reading. This was one of my favorites:

So Then She

With flour and water she worked

his body. With flour and saliva

she conceived, leaned, learned

that with flour and both hands you reach

the secret pliability of matter.

With flour and lips she worked

the man down to the unbearable

elasticity of tenderness.

The slowly she tasted

his body, the bread that was his body,

bread that fit as well in her hands

as does light on earth.

§§§

What’s The Meaning of Hanukkah?, by Mendele Moykher-Sforim, translated by Ri J. Turner:

“Anyway, the slap itself,” Shmuel went on, “wouldn’t even be worth mentioning if it hadn’t ultimately caused an upheaval that led me to discover new ideas. Basically, the slap I received from my father was not in vain. The whole discussion of Hanukkah, my father’s anger, the unexpected slap—it all remained vivid in my memory and drove me at quite a young age to chew on the question, ‘What’s the meaning of Hanukkah?’”

This story—the source does not give the date of original publication, only that it can be found in volume 9 of Moykher-Sforim’s collected works—devolves upon the kind of question that would lead many teachers to characterize the asker as a smart-ass: “The story about the single jar of oil that should have lasted only one day but lit the sanctuary for eight didn’t make [any] sense. If that’s how it happened, then the miracle itself only lasted for seven days—so why introduce an eight-day holiday?” That question leads the narrator to open “an extra-canonical book—a book of Jewish history,” and it’s there that his “eyes were opened and [he] found an answer” to the question which gives the story its title. I don’t want to say more, because I think part of the story’s genius is that the narrator does not articulate this answer himself. Rather, Moykher-Sforim leaves it up to the reader to figure out what the narrator means. The only caveat I will add is that the story does assume a knowledge of Jewish culture, nothing that isn’t easy enough to look up, though I think it’s possible to understand the story without doing so. Much of the story’s humor is embedded in that cultural knowledge.

§§§

The True Glory of the Maccabean Revolt: What Liberty was Fought For?, by Theodor Gaster:

Thus, the [Maccabean Revolt] had two objectives. First, it was designed to safeguard the actual identity of the Jews… Second, the resistance was designed to safeguard the constitutional status quo. In this, Mattathias and his followers were championing a cause which, transcending the particular interests of the Jews, extended also to all the national groups within the empire.

Years ago, at a gathering of my wife’s family that happened around Chanukah, a woman who was not Jewish apologized to me for not wishing me a happy holiday because she refused to celebrate an imperialist, nationalist holiday. She did not need to tell me, because I already knew her well enough, that this “apology” emerged from her anti-Zionist critique of the State of Israel and her corresponding support for Palestinian liberation. I did not bother to argue with her for two reasons. First, because I knew that pointing out the ahistorical nature of her position would do no good and, second, because it would be pointless to deny that Jews often do, very publicly, frame the existence of the State of Israel as being precisely the kind of thing that the Maccabees fought for. I have neither heard or read anyone making that kind of argument these days, which doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen, but I take it as a hopeful sign nonetheless, especially given the ongoing devastation Israel is unapologetically wreaking on the Palestinians. Still, I was glad to come upon this article, from the December 1952 issue of Commentary. Especially towards the end I found much to disagree with (in no small measure because the world is very different seventy plus years after it was published), but Gaster does two things that I think are especially valuable for today. First, as I allude to in the quoted portion above, he points out that the oppressive policies under which the Jews suffered were targeted not only at Jews, but at all religious groups that were not part of Antiochus’ state church, formed in pursuit of (an enforced) political unity that had not previously existed and that he hoped would present “a united front against the ambitions of Rome on the one hand and of the rival power of the Ptolemies on the other…” Second, Gaster reminds us that the Maccabees were neither a majority movement within the Jewish community nor what we would call progressive, or even liberal, in their ambitions. In fact, given the ways in which they forced other Jews to practice as they did, the Maccabees had a lot in common with what the religious extremists of today say they want. It’s important, in other words, not to romanticize the Maccabees by turning them into the kind of liberators we would want them to be; and it is equally important to remember that, while they were unquestionably fighting to free the Jews from Antiochus’ oppression, they also understood, at least according to Gaster’s analysis, that their freedom to practice Judaism on their own terms was inseparable from the freedom of other religious communities to practice their faiths in the same way.

§§§

Rest in Power: A Running List of the Preventable Deaths Caused by Abortion Bans, Roxanne Szal:

These women should be alive today…Ms. is marking [their] stories. This article will be updated to mark every single name made public.

I don’t think I need to write much more than that quote. It is important to read through this unconscionably-too-long list and to remember as you do so that, as Szal puts it, “[T]hese are likely not the only cases, as there has been a significant increase in maternal mortality rates in states that implement strict abortion bans.”Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

All these images are posted on X by Jewish Art:

Hannukiah, by Randy Suzker

§§§

Hanukkah, by Karin Foreman

§§§

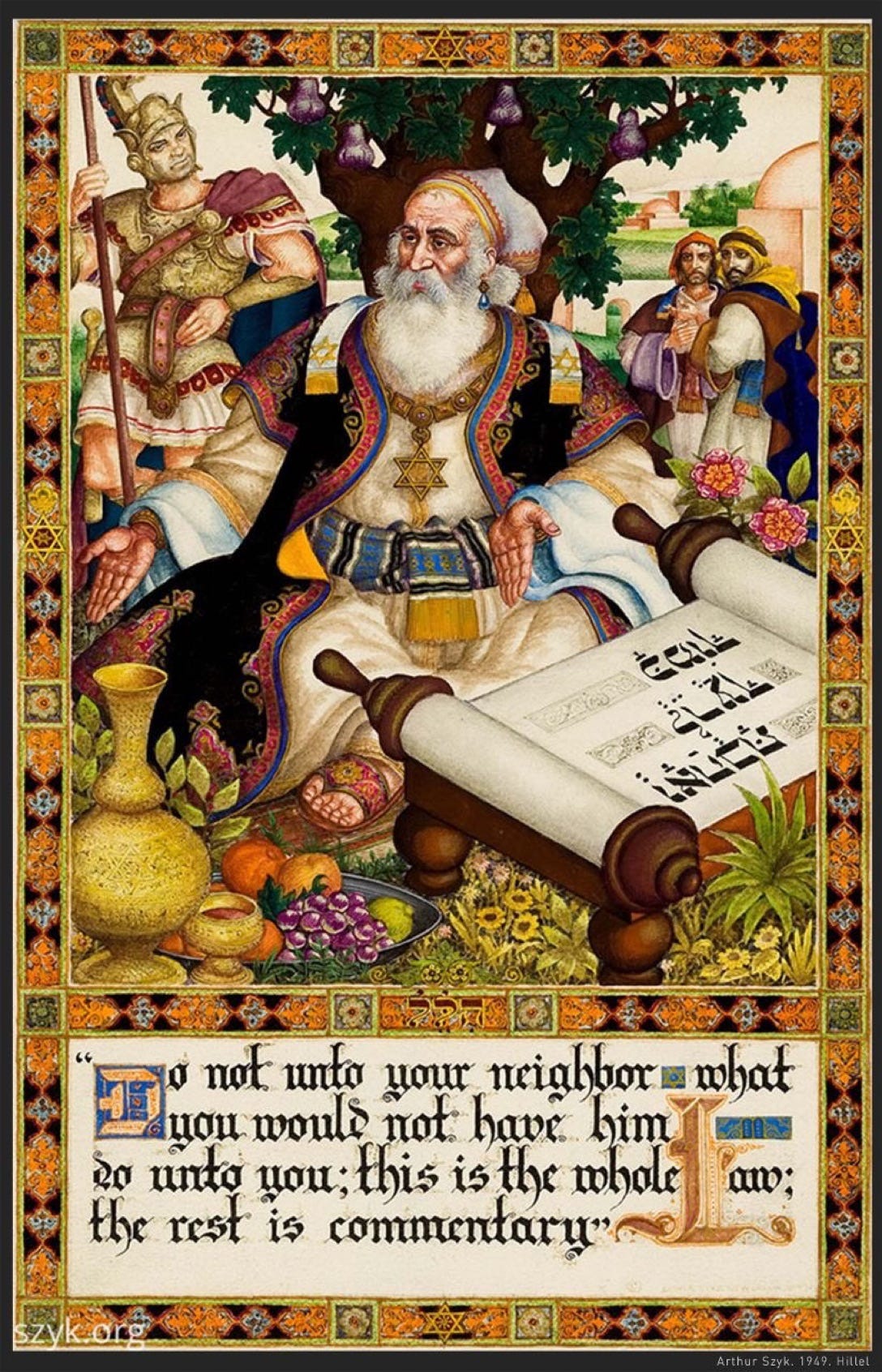

Rabbi Hillel, by Arthur Szyk

Note the difference between the way Hillel states “The Golden Rule,” in the negative (Do not unto your neighbor), and the positive statement that is more commonly quoted (Do unto your neighbor).

§§§

Kletzmer #1, by Itzchak Fleisheker (IZIK)

Four Things To Listen To

Sevivon Sov, Sov, Sov - Kenny Ellis

§§§

Applesauce vs. Sour Cream - The Leevees

§§§

Ocho kandelikas - Pink Martini ft. China Forbes, Ari Shapiro, Storm Large and Cantor Ida Rae Cahana

§§§

Hanukkah Dance - Woody Guthrie

Four Things About Me

My father and I did not speak for about ten years, from the time I was twenty-one or twenty-two until I was in my early thirties. Much had changed in my life during that time–I’d gotten married, for one–and so there was a lot about me that my father didn’t know. One of the ways I tried to catch him up on the person I’d become, as it were, was to give him a sheaf of poems that I’d written during those years. I had no idea how he would receive them or what he would think of my being a poet—he worked on Wall Street and was not much for the arts—but the conversation we ended up having surprised me in a way I could never have anticipated. We were walking somewhere in Manhattan, when he turned to me and said—and I promise you this is how my father really talked—“I read your poems. I also gave them to Alline [his wife] to read, since, you know, I’m not much of a reader. She and I talked about it, and I have to ask you a question. It’s kind of a joke, but it’s also not, if you know what I mean. So here’s the question, and I guess I’ll understand if you don’t want to answer at all, but remember, I am kind of joking when I ask this, even though I’m also being very serious. There’s a line in one of the poems you wrote when you were teaching in Korea, something about ‘the bodies I have buried in my imagination.’ Did you actually kill someone when you were teaching there?” The poem itself is long gone, and I remember nothing else about it except that line, so I can’t tell you whose bodies they were, if they were identified at all, or what happened to them. All I can say, since I know I did not commit murder while living in Seoul, is that they were, and should have been clearly recognizable as, a metaphor. My father, however, was not interested in talking about why or how he had misread my poem. All he wanted to know was whether I’d left a pile of bodies back in Korea when I came back to the United States. So I reassured him that I hadn’t, and that was the first of only two times that we ever discussed my work as a writer.

§§§

The second time my father and I talked about my writing, was in the Union Square Barnes & Noble. We were standing in the children’s section, watching my son lead my wife around to the different bookshelves. He loved bookstores, my son, so much so that when we took him to the ones closer to our home, we were often the last customers in the store. Anyway, I needed to use the bathroom, which was on the same floor as the poetry section, so when I was finished, I went to spend a few minutes checking the shelves, just to see if there was anything interesting. I was happily surprised to see a copy of Beyond Lament: Poets of the World Bearing Witness to the Holocaust, an anthology in which some of my poems had been published. I took the book upstairs to show my father, thinking he’d get a kick out of seeing my name in a book being sold in an actual bookstore. I handed the book to him, opened to the page where he could see my name. He smiled, made a show reading one of the poems—in reality I could see that he’d scanned the page and nothing more—and said, “Wow, Rich, that’s really deep.” Then my father did something that I still don’t fully comprehend. He closed the book, glanced left, then right, and then left again. Leaning towards me as he held open the left side of his London Fog raincoat, he gestured with his eyes towards the inside pocket, saying sotto voce, “You know, Richie, if I were a younger man…” and he inclined his head ever so slightly to the left, making it clear, if I hadn’t gotten it before, that the impulse to steal the book that he was choosing not to act on was a sign of respect for the fact that my work had been published within it. That was the last time I ever spoke with my father about my poetry.

§§§

It’s one thing to know that sexist erasure exists, to read about it, learn about its mechanisms, and so on. It’s quite another thing to watch as it happens before your eyes. Built in the 1920s, the co-op where I live in New York City is a historical landmark that went into receivership in the 1930s, during the Depression, and remained a rental property until the 1970s, when a group of tenants organized themselves to transform the place once again into a co-op. My grandmother was central to that effort. Not only was she involved in the whole process of incorporation; she was also the co-op’s first manager and the first president of the board. She was also intimately involved in the Garden Committee from its inception. The co-op recently celebrated its 100th year anniversary with a big celebration that included not only a party for shareholders, but, given our buildings’ historical significance, proclamations from local politicians. In the run-up to the celebration, one of the organizers got in touch with me to ask if I had any pictures of the grounds from my grandmother’s time. I did not. Based on that question, though, I assumed that the organizers—some of whom were old enough to know better than I how deeply involved my grandmother had been—were of course going to include her in whatever programming they had planned. I was wrong. On the day of the celebration, as I walked around, I met more than a few people who remembered my grandmother and all the work she did. Some of them had known me when I was a little boy. When it came time for the speeches, however, and for the proclamations, not one person mentioned my grandmother’s name among the list of men who were being remembered, nor did any of the people who knew her back then seem to notice, until I mentioned it to one of them. She was appropriately surprised and embarrassed by the omission, and she said she was going to rectify the situation. I have not heard from her about it, though, and so I am assuming nothing was done. What is clear to me, though, is that, had my grandmother, the only woman among the men who’d been honored, also been a man, she would not have been left out in the first place.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion