Four Things To Read

Fabulous Beast, by Sarah Kain Gutowski: Fabulous Beast is divided into three sections—“The Sow,” “The Woman With The Frog Tongue,” and “Minor Gods”—that are bookended by a prologue and epilogue. The prologue and epilogue frame the book as an exchange between mother and daughter in which, broadly speaking, the three inner sections are stories the mother tells to explain things to her daughter about what it means to be a woman and a mother in a world where very specific and idealized versions motherhood and womanhood might be valued, but actual women and mothers are systematically devalued and dehumanized. That programmatic and overtly political nature of that description, however, does not do the book justice. This is a book of poetry, not a polemic. Gutowski’s concern—animated without question by a feminist perspective—is less about, for example, making women’s oppression per se visible than it is about capturing, with all its internal contradictions and ironies, the interior experience of trying to build a meaningful life as a woman and/or a mother under the terms that oppression imposes. She does this by weaving the women she writes about into narratives built from elements of fairy tale, myth, and even horror. Neither the sow, nor the woman with the frog tongue, nor the woman who appears in “Minor Gods,” in other words, is a crusader in any obvious sense of that term; and much of the book’s power derives from the fact that none of the sections—each of which deserves a review on its own terms—resolves in an obvious, polemical manner. I think it would be very interesting to read Fabulous Beast next to Julia Kolchinsky Dashach’s 40 Weeks, which is also about motherhood and which I wrote about in Four by Four #17, and I found it really interesting that Gutowski’s “Mama, Couldn’t She Eat a Fly? Because She Has a Frog Tongue,” in which the woman with the frog tongue has a dream about her arm detaching itself from her body, immediately recalled for me the protagonist of Moon Brow, by Shahriar Mandanipour (translated by Sara Khalili), who spends the entire novel searching for the arm he lost in Iran’s war with Iraq. I have not thought deeply about this connection, but it might be something worth pursuing. The last thing I will say about Fabulous Beast is how much I admire how well-crafted the poems are. In her notes Gutowski says that the form of “The Woman With The Frog Tongue” is based on Edmund Spenser’s “The Faerie Queen,” and what she does with the form is really interesting, but you can tell that Gutowski paid the same careful attention to form in the other two sections as well. The language of these poems is orchestrated, in every sense of that term, and they bear study on that level.

§§§

William Labov, Who Studied How Society Shapes Language, Dies at 97, by Clay Risen:

In one famous study, he went to three department stores in New York City — high-end Saks Fifth Avenue, middle-class Macy’s and budget-level S. Klein — and asked for an item he knew was on the third or fourth floor. What he found confirmed his hypothesis that the New York accent was shaped not just by region but by class: The more expensive the store, the more likely he was to hear the “r’s” in “fourth floor.” What was more, he recognized that the salespeople he asked at Saks were unlikely to be upper class themselves — instead, he concluded, they code-switched to a type of speech that fit their customers.

I studied Labov’s work when I was a graduate student in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) at Stony Brook University. I remember well our discussion of this study’s relevance to what it means for an adult English-language learner to try to make sense of the different registers of the language they would be likely to encounter in their daily lives. The truly eye-opening aspect of Labov’s work, however, at least to me, was his study of what was then called Black English, but has since been called by a range of names, including African American Vernacular English and Ebonics. The book he wrote is called “Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black English Vernacular.” I don’t remember if we read the entire book, but I was deeply moved by the way his study exposed the racism inherent in the promotion of the variety of English I spoke as not just the only correct way to speak, but also the only one that could truly be called a language. He distilled much of what he had to say in that book for a popular audience in a 1972 article he wrote for The Atlantic called “Academic Ignorance and Black Intelligence.” I started using this article to introduce the grammar class I taught because I was surprised by how many students who registered for the class held some (admittedly watered-down ) version of the beliefs about African American Vernacular English (AAVE) that Labov was fighting against:

The most extreme view which proceeds from [the deficit model of understanding AAVE]—and one that is now being widely accepted—is that lower-class black children have no language at all. Some educational psychologists first draw from the writings of the British social psychologist Basil Bernstein the idea that “much of lower-class language consists of a kind of incidental ‘emotional accompaniment’ to action here and now.” Bernstein’s views are filtered through a strong bias against all forms of working-class behavior, so that he sees middle-class language as superior in every respect–as “more abstract, and necessarily somewhat more flexible, detailed and subtle.” One can proceed through a range of such views until one comes to the practical program of Carl Bereiter, Siegfried Engelmann, and their associates. Bereiter’s program for an academically oriented preschool is based upon the premise that black children must have a language which they can learn, and their empirical findings that these children come to school without such a language.

This article is still worth reading today, as is the obituary I linked to initially.

§§§

Boneyarn, by David Mills: The subject of this collection is the Negro Burial Ground in what is now Lower Manhattan: the land itself; the people buried there; the politics, of slavery and otherwise, that led to the founding of the cemetery; and more. I think I might have known the Burial Ground existed before I read this book, but I had no idea just how disturbing and complex the history behind it is, ignorant as I am about the legacy of slavery here New York City, where we like to think of ourselves as always having been “above such things.” Indeed, each time I referred to the notes Mills provides, I found myself wishing that Ashland Poetry Press had published the poems as part of a two-volume set, with the other volume containing the history that Mills has to fill in so that a reader will have better access to the many-layered richness he’s packed into the poems themselves. You don’t necessarily need the history to appreciate the poems, but since part of the purpose of this book is clearly to educate, it would have been interesting to see how knowing a fuller historical context would have changed the way the poems “hit.” The strongest poems in the book break down into two categories: those like “Chimney Sweep Apprentice” or “Coating: Warwick” in which Mills inhabits the voices of the people he learned about through his research and those like the ones titled “Talking To The Bones,” in which he imagines himself into the allusive, enigmatic, and epigrammatic, voices of the bones of the dead. Throughout the book, I enjoyed watching Mills’ work through the challenge of finding the forms—poetic, syntactic, rhythmic—that would hold this history that so few people know about, and I would remiss if I did not note, as I did talking about Fabulous Beast above, the pleasure I often took in letting the finely tuned music of Mills’ poetry wash over me. Finally, the section titled “Jupiter & Wheatley’s Suite,” sent me back to an essay I had not read in several decades, June Jordan’s “[The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America”][ Something like a sonnet for Phillis Wheatley](https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/68628/the-difficult-miracle-of-black-poetry-in-america).” It’s an essay worth reading next to David Mills’ book.

§§§

Things Not Seen, by Hrag Vartanian and Valentina Di Liscia:

A wave of anti-Palestinian repression has swept the Western art world in the aftermath of October 7th, 2023. From Amsterdam to San Francisco, artists who have criticized Israel’s brutal war on Gaza have seen their exhibitions canceled, their work deinstalled, and other opportunities rescinded.”

This article catalogues thirteen pieces of art that were, in the words of the authors, “either targeted by cultural entities or removed in protest” because of the artists’ stance regarding Israel and Palestine. I don’t have the rights to reproduce any of that art work in the “Four Things To See” section below, but reading the article reminded me of “Sun City,” a protest song from the anti-apartheid movement in the United States produced in the 1980s by Artists United Against Apartheid. I’ve included a YouTube video in the “Four Things To Listen To” section.

Four Things To See

These images are all from the Library of Congress and are all in the public domain.

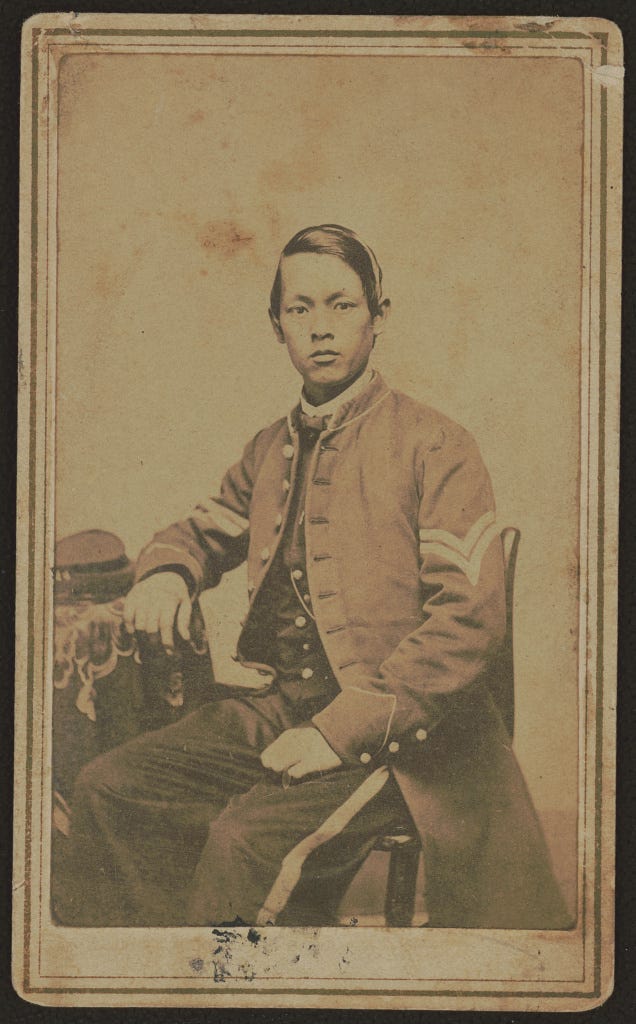

Corporal Joseph Pierce

Corporal Joseph Pierce of Co. F, 14th Connecticut Infantry Regiment achieved the highest rank for a Chinese American soldier during the Civil War. (Photo by William Hunt, 1862-1865)

§§§

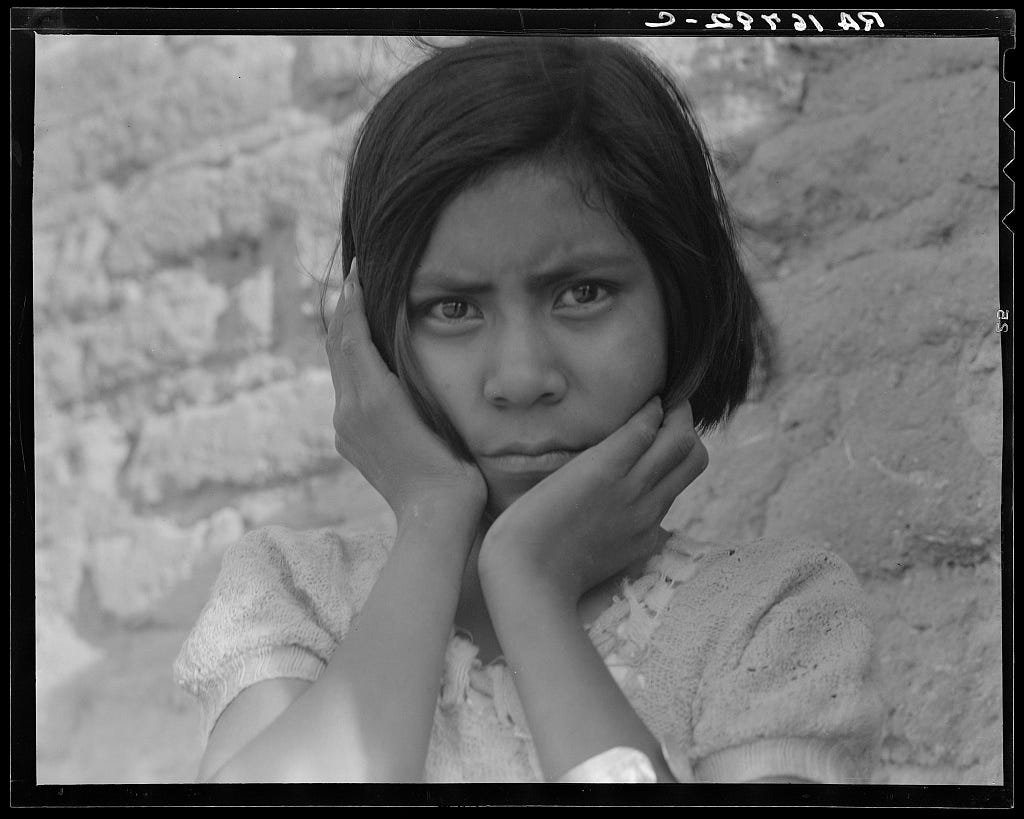

Daughter of a Mexican Field Worker

Photograph by Dorothea Lange, May 1937

§§§

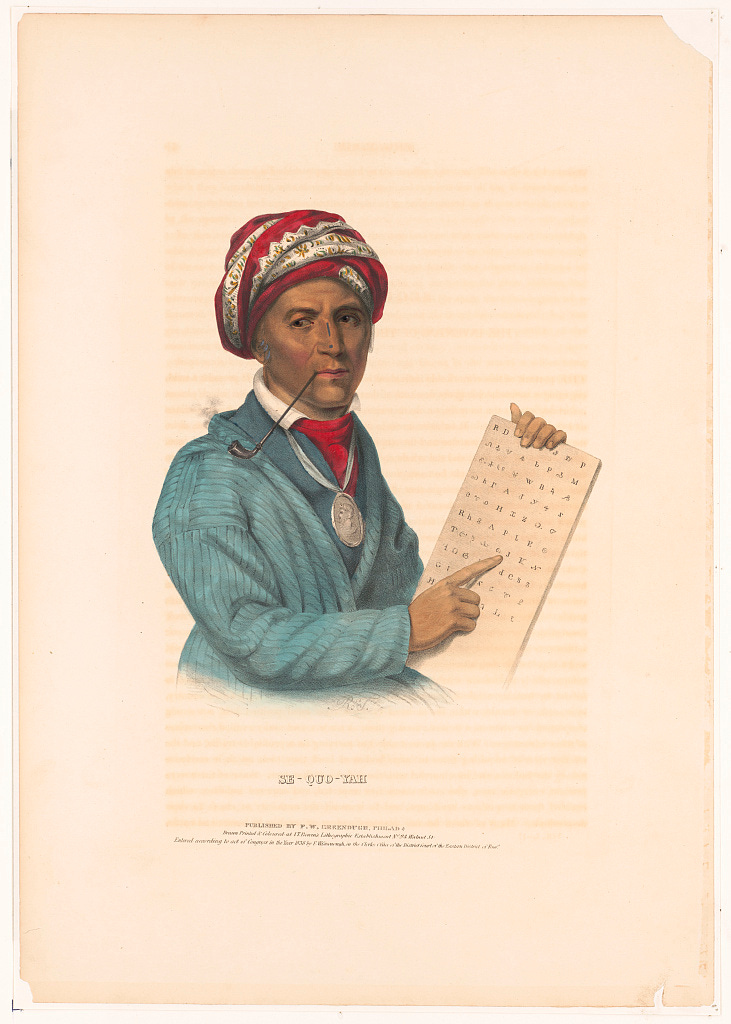

Sequoyah, holding the syllabary he created for writing the Cherokee language

Portriat print by John T. Bowen, 1838

§§§

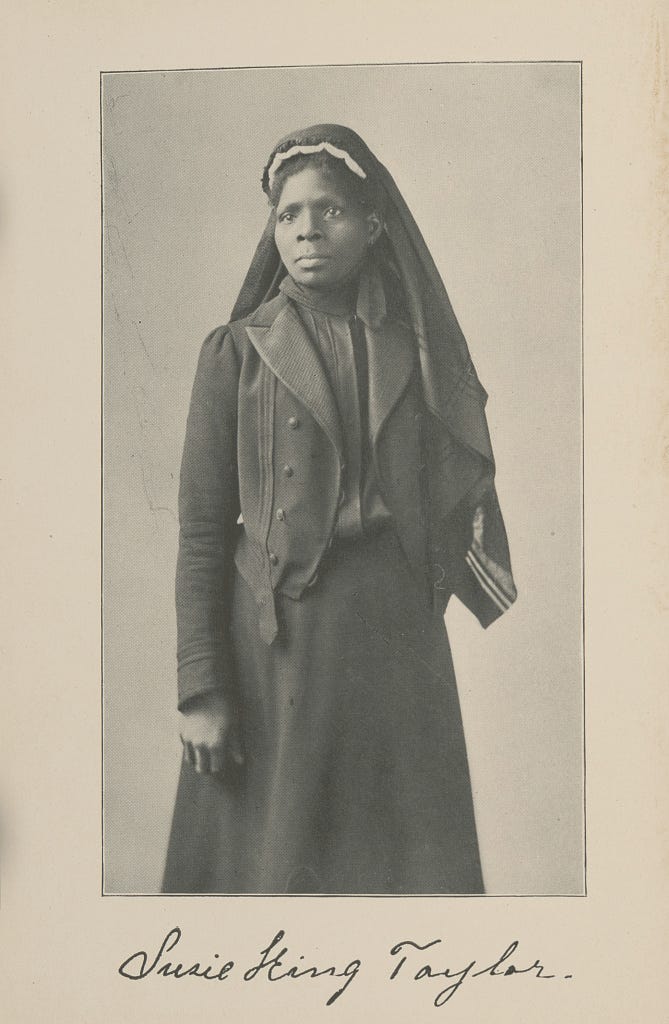

Photograph of a portrait of Susie King Taylor

Susie King Taylor served more than three years as nurse with the 33rd U.S. Colored Troops Infantry Regiment during the American Civil War, although officially enrolled as a laundress. She also taught children and adults to read while serving with the regiment.

Four Things To Listen To

Sun City - Artists United Against Apartheid

This is from Wikipedia: Steven van Zandt, upset by the fact that artists from Europe and North America were willing to perform in Sun City, a whites-only luxury resort in the “homeland” of Bophutatswana, persuaded artists including Bono, Bruce Springsteen, and Miles Davis, to come together to record the single “Sun City,” which was released in 1985. The single achieved its aim of stigmatizing the resort. The album was described as the “most political of all of the charity rock albums of the 1980s.” “Sun City” was explicitly critical of the foreign policy of U.S. President Ronald Reagan, stating that he had failed to take firm action against apartheid. As a result, only about half of American radio stations played “Sun City.” Meanwhile, “Sun City” was a major success in countries where there was little or no radio station resistance to the record or its messages, reaching No. 4 in Australia, No. 10 in Canada and No. 21 in the UK.

§§§

The Puppet Who Dances BeBop - The Barbara Carroll Trio

§§§

Venus / Zohreh - Shiva Feshareki

§§§

Quando spiega l'insegn' al sommo padre - Paola Massarenghi

Four Things About Me

When I switched from public school to yeshiva after seventh grade, I was one of the top students in my class. I don’t remember if I had the highest grades, but I am pretty sure I was in the top five percent, if not higher. As I recall, I did not want to switch schools, but someone—I don’t think I ever knew who—offered me a full scholarship based on how fully I embraced what I was learning about being Jewish in the after-school Talmud Torah I’d been attending and on my stated desire at the time to be orthodox when I grew up. (My family was not observant.) My mother and my grandparents thought it would be foolish to turn the offer down, though their reasoning had nothing to do with religion. They were convinced I would get a better education in the yeshiva than I would in public school. In some ways, they may have been right. The experience of “learning Torah” trained me in a kind of critical thinking that I don’t think would have been back then part of a high school public education, but an equally important lesson, one that I have carried with me ever since, is just how corrosive an overemphasis on getting good grades—which there meant getting straight A’s—could be. It wasn’t that I thought doing well was unimportant, but watching how unhappy my top-of-the-class classmates were as they stressed over whether or not they would ace their entire report card—to win their parents’ approval, to get into the college they wanted to go to, or some combination of both—helped me begin to understand that getting a good grade was not necessarily the same thing as truly learning something. That distinction remains to this day a central part of my pedagogy.

§§§

We graduated from the yeshiva with our high school diplomas in 11th grade. We could choose from three options for how to spend the following year. You could go to Israel to learn Torah in a yeshiva; you could attend a special program in which you learned Torah in the morning and took college classes in the afternoon; or you could go back to public school for 12th grade. I opted for the third choice, but I was completely unprepared for how I was received by the people who had been my classmates in sixth and seventh grade. Some of them, for example, would not talk to me until they found out that my class ranking was lower than theirs. One episode remains firmly fixed in my memory. A girl named Debbie, along with whom I had been one of the top two students in sixth grade, asked to see my schedule. Since I had already fulfilled all my graduation requirements, I had been enrolled in only one AP class, English, and the rest of my schedule was filled out with electives. Debbie—who, like all the students at the top of our class, was enrolled in all the AP classes that were available to her—tossed my schedule dismissively back onto my desk. “What did they teach you at that fancy, private school? To be lazy?” I don’t think she said two words to me for the entire rest of the year.

§§§

I started losing my hair when I was around fifteen years old, which meant that, by the time I reached 12th grade, I looked older, sometimes a lot older, than my classmates. This, coupled with the fact that I had come back to the school as a senior, led to one of the strangest rumors about me that I’ve ever heard. Spread mostly by people who had not known me before, the rumor stated that, along the lines of 21 Jump Street, I was a narc, planted in the school to root out my classmates who were selling drugs. This, of course, was not true, though it was true that the neighborhood in which I lived, being on the border of Queens and Nassau County, was at the time one of, if not the primary conduit through which drugs traveled from New York City to Long Island. Ironically, in the months after graduation, an undercover narcotics squad conducted a huge sting operation just a few blocks away from where I lived. They arrested more than a few of the kids who were in my graduating class.

§§§

One of the most embarrassing moments of my senior year in public school took place in AP English. We were discussing “To His Coy Mistress,” by Andrew Marvell. Our teacher asked if anyone knew the biblical reference in the last couplet:

Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will make him run.

I was the only one to raise my hand. I doubt I remembered the specific chapter and verse, Joshua 10:12–14, but I did know that the lines refer to the battle between the Israelites and the Amorites, in which God gave Joshua the power to tell the sun to stand still until the battle was done and the Israelites were victorious. After I gave my answer, Mr. Giglio put his book down and looked disapprovingly over the class. “That story was part of Sunday’s reading in Church. How is it that this boy who does not even go to Church knew Marvell’s allusion, while not one of the rest of you did?”

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

A poet and essayist, I write about gender and sexuality, Jewish identity and culture, writing and translation. My goal? To make connections that matter. I also help other writers do the same.