Four Things To Read

Mortals, by John Dermot Woods and Matt L: The frontispiece of this graphic novel, which is repeated on the book’s final page, is an illustration of the riddle, What goes on four legs in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three in the evening?The answer is a human being, who crawls as an infant, walks on two legs through the middle of their life, and needs a cane when they are older—except that the frontispiece has the person, in this case a man, running instead of walking. The riddle, which is never stated explicitly, frames the development of the book’s main character, a man named Francis. Francis is a married-soon-to-be-divorced father, though you don’t know that until it actually happens. He’s also an actor—a very self-involved one, at least at first, so much so that he doesn’t even remember the name of his son’s best friend, whom we learn at the beginning of the book has died. The rest of the story, broadly speaking, traces Francis’ confrontation with his own mortality, and how that plays out in his relationship with others, especially his son and his ex-wife, and with himself as a father and an artist. One of the strengths of this book is the way that the kind of commentary that would be necessary in a traditional novel and that could easily come across as didactic or moralizing is rendered implicit in the artwork. For me, the most interesting part of that confrontation—which is divided into three sections that correspond to the three “ages of man” that are the answer to the riddle—is how Francis comes to terms with the fact that he’s been using his desire to be a serious artist, his commitment to not selling out, as a way to avoid the humility and vulnerability that are required to make art in the first place. I recommend this book.

§§§

Five Journalists in Gaza Reflect on Ceasefire Announcement, by Sharif Abdel Kouddus (who also translated the journalists’ Arabic into English):

My feelings when I heard the announcement — I saw the happiness of people and their tears of joy. But with regard to myself, as a journalist and a human being and a Palestinian who lives in north Gaza, I have contradictory feelings ranging from joy to sorrow. I lost nearly 250 members of my family. Relatives of relatives: my nephews, nieces, aunts, their sons and daughters, my uncles and their wives and children. I lost a very large number of people. We are one of the families that has the highest number of martyrs in this genocidal war.

—Bilal Salem, Gaza City. A 37-year-old journalist from Gaza City. He is a member of the Salem family who have lost over 270 members in different Israeli attacks.

As the title says, this article collects the responses to the recently negotiated cease fire between Israel and Hamas of five Palestinian journalist who currently live in Gaza. I am sharing it with you not because I have anything to add, but because these are voices you will not hear in the mainstream media, where the cease fire will no doubt be covered as an unmitigated triumph and as a sign that it’s time for both sides to begin the long process of “putting the war behind them,” as if the war had been a symmetrical one, in which each side had suffered equally. I don’t mean, of course, that Israelis, especially the hostages and their families, friends, and loved ones, did not suffer; but to suggest that the ceasefire means the same thing to each side or that it is—as people have tried to characterize October 7—separate and distinct from the entire history of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, as the mainstream media is likely to do, is at best a cynically disingenuous silencing of voices like the ones Kouddus shares in this article.

§§§

No, Katherine Franke Was Not Fired, by Steven Lubert:

My research for this article included an examination of the public record, a review of Columbia’s final Investigation Determination (which has not been made public), information provided by university employees about the extensive findings in the underlying Investigation Report, exhibits attached to Franke’s appeal, and other relevant documents. I learned that Franke did not face discipline because she “referenced a history of harassment against Palestinians,” or for her “support of pro-Palestinian protesters.” Rather, two outside investigators concluded that, in an interview with Democracy Now! on January 25, 2024, she had “subjected Israeli members of the Columbia community to discriminatory harassment.”

Lubert wrote this piece in response to the one-sided coverage of Katherine Franke’s decision to leave Columbia University, where she had been the James L. Dohr Professor of Law at Columbia University and Founder/Director of the Center for Gender & Sexuality Law. In a statement she released on January 10, 2025 Franke characterized the end of her tenure at Columbia as the “termination [of her employment] dressed up in [the] more palatable terms [of retirement],” resulting from her defense of “students’ right to peaceful protest” in support of the “rights and dignity of Palestinians.” Lubert’s article complicates that picture in important ways, providing information that Franke leaves out of her account, as well as a perspective that is rooted less in polemic or ideology than in a desire for factual accuracy.

That said, there is no question that Columbia University’s administration, along with many other colleges and universities across the country, has been both exceptionally hostile to pro-Palestinian voices and overly solicitous of those voices that are pro-Israel. In that context, it is easy to take Franke at her word when she says

[T]he University has allowed its own disciplinary process to be weaponized against members of our community, including myself. I have been targeted for my support of pro-Palestinian protesters – by the president of Columbia University, by several colleagues, by university trustees, and by outside actors. This has included an unjustified finding by the University that my public comments condemning attacks against student protesters violated university non-discrimination policy.

Franke made those comments in an interview with Democracy Now:

Columbia has a program. It’s a graduate relationship with older students from other countries, including Israel. And it’s something that many of us were concerned about, because so many of those Israeli students, who then come to the Columbia campus, are coming right out of their military service. And they’ve been known to harass Palestinian and other students on our campus. And it’s something the university has not taken seriously in the past. (My italics)

The non-italicized portion of that quote, according to the outside investigators cited by Lubert constituted a Title VI violation in that it “lacked a factual basis and constituted a negative, unfounded stereotype about Israeli students, who comprise a protected class.” Lubert also points out that the law firm hired by the university to conduct this investigation found “[b]ased on multiple interviews…that Franke’s comment had an adverse impact on Israeli students, causing them to experience isolation and distress and contributing to a hostile learning environment.”

While it’s unlikely that a similar generalization made in a less volatile context about any other protected class, assuming they were not part of a larger pattern and amounted to a sentence or two uttered during a media interview, would have resulted in a professor’s dismissal, I don’t think anyone would disagree that the professor who made those comments would need to be called to account. Nonetheless, there’s a lot to unpack here. Israelis, for example, and especially former Israeli soldiers, being citizens of a country that is waging a genocidal war against a relatively helpless population, are easy targets. More than that, because it’s “easy” to dismiss the kind of generalization Franke made because of its “trivial” nature when compared to the devastation Israel is wreaking in Gaza, it is easy to paint anyone who wants to hold someone like Franke accountable as at best “not getting it” and, at worst, an apologist for genocide. Then there’s the fact that Lubert’s appeal to objectivity conveniently elides Columbia’s anti-Palestinian hostility as the context in which the whole affair needs to be understood. To ignore that context, after all, is to avoid the question of why the consequences to Franke of a single inappropriate sentence in a media interview should have such absolute consequences. There’s more, but to get into that would require an entire essay.

§§§

Why Is a Publisher of Antisemitic and Homophobic Authors Winning a National Book Award?, by Mark Oppenheimer:

Even in our busy news season, a time of elections and wars, one might have thought that the announcement that a National Book Award will be given next month to a purveyor of antisemitic and homophobic tracts would have caused a bit more of a stir. It seems like the kind of story that would be picked up by major newspapers, public radio, or, at the very least, the trade magazines whose sole purpose is to cover publishing. It is remarkable, then, that there has not been greater attention to the work of William Paul Coates, who will receive the award on Nov. 20. As the publisher of The Jewish Onslaught, as well as assorted other books, Coates has promoted writing that is, in the parlance of our time, problematic, promoting pseudoscience while demeaning Jews and gays, among others.

Were it the case that Coates’ press, Black Classic Press (BCP), published these book while providing some kind of critical or historical context that explained why it was important to publish them, despite their “problematic” nature, the fact that he’s receiving the award would not be an issue. After all, there are presses, to pick an obvious example, that make sure to provide contextual apparatus for the editions of Mein Kampf that they publish. Oppenheimer details the problematic books in BCP’s catalogue, including, along with The Jewish Onslaught, titles like Chosen People from the Caucasus: Jewish Origins, Delusions, Deceptions and Historical Role in the Slave Trade, Genocide and Cultural Colonization; The Jewish Onslaught: Despatches from the Wellesley Battlefront, and We the Black Jews: Witness to the “White Jewish Race” Myth and African Origins of the Major Western Religions. Most interestingly, and tellingly, Oppenheimer documents the fact that “Tactics of Organized Jewry in Suppressing Free Speech,” a speech by Tony Martin, author of The Jewish Onslaught, can be bought either from Black Classic Press or the website of the Institute for Historical Review (IHR), a Holocaust-denial organization.

Two things stand out for me: The fact that the National Book Foundation was willing to give Coates the award despite the unapologetic presence of those books in his catalogue seems to me clearly to demonstrate a double standard in how we respond when it comes to antisemitism versus other forms hatred. Also, the fact that the same text is available both from Black Classic Press and the Institute for Historical Review makes it very clear that this double standard exists at least in part because antisemitism is the exclusive purview of neither the left nor the right.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Four Things To See

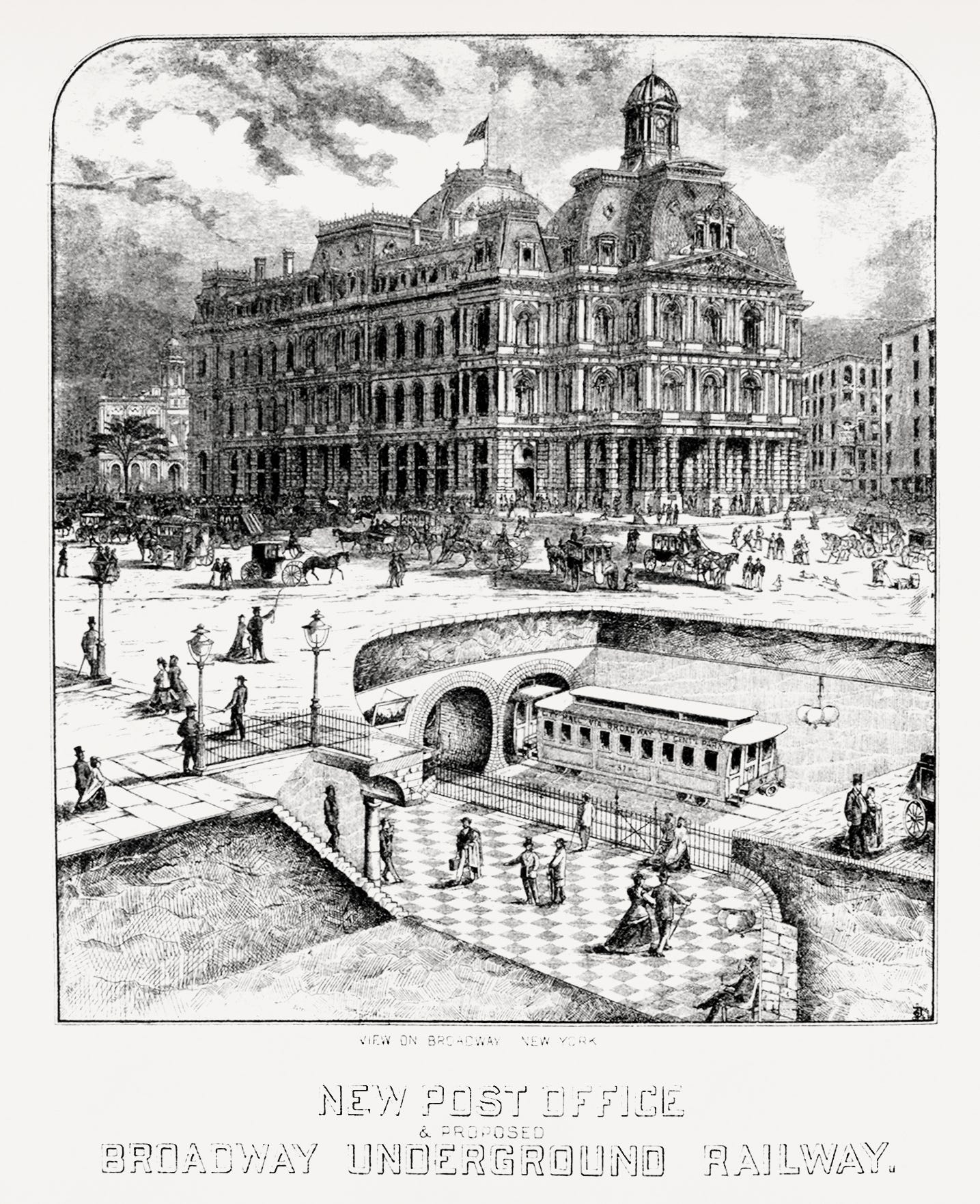

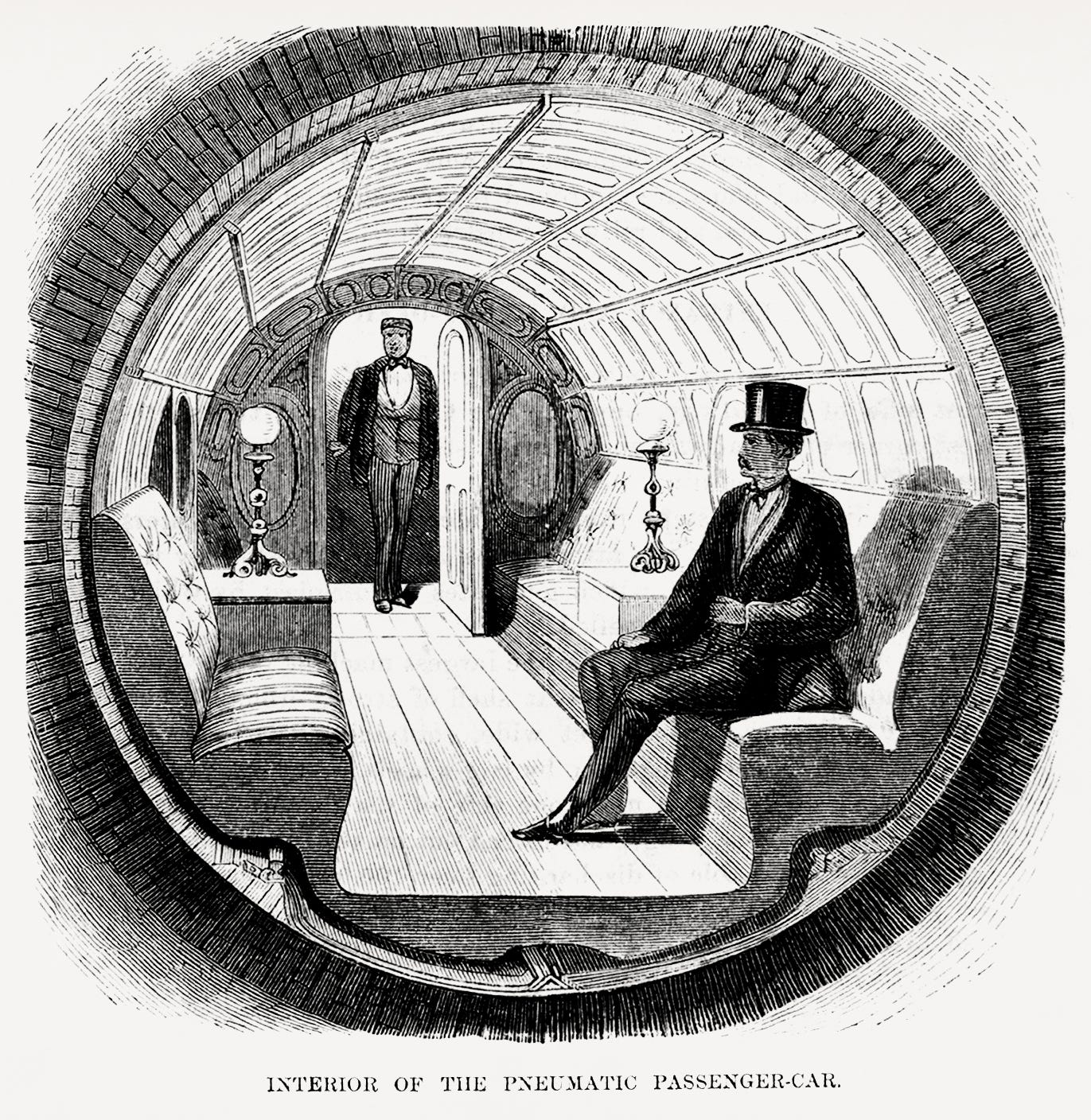

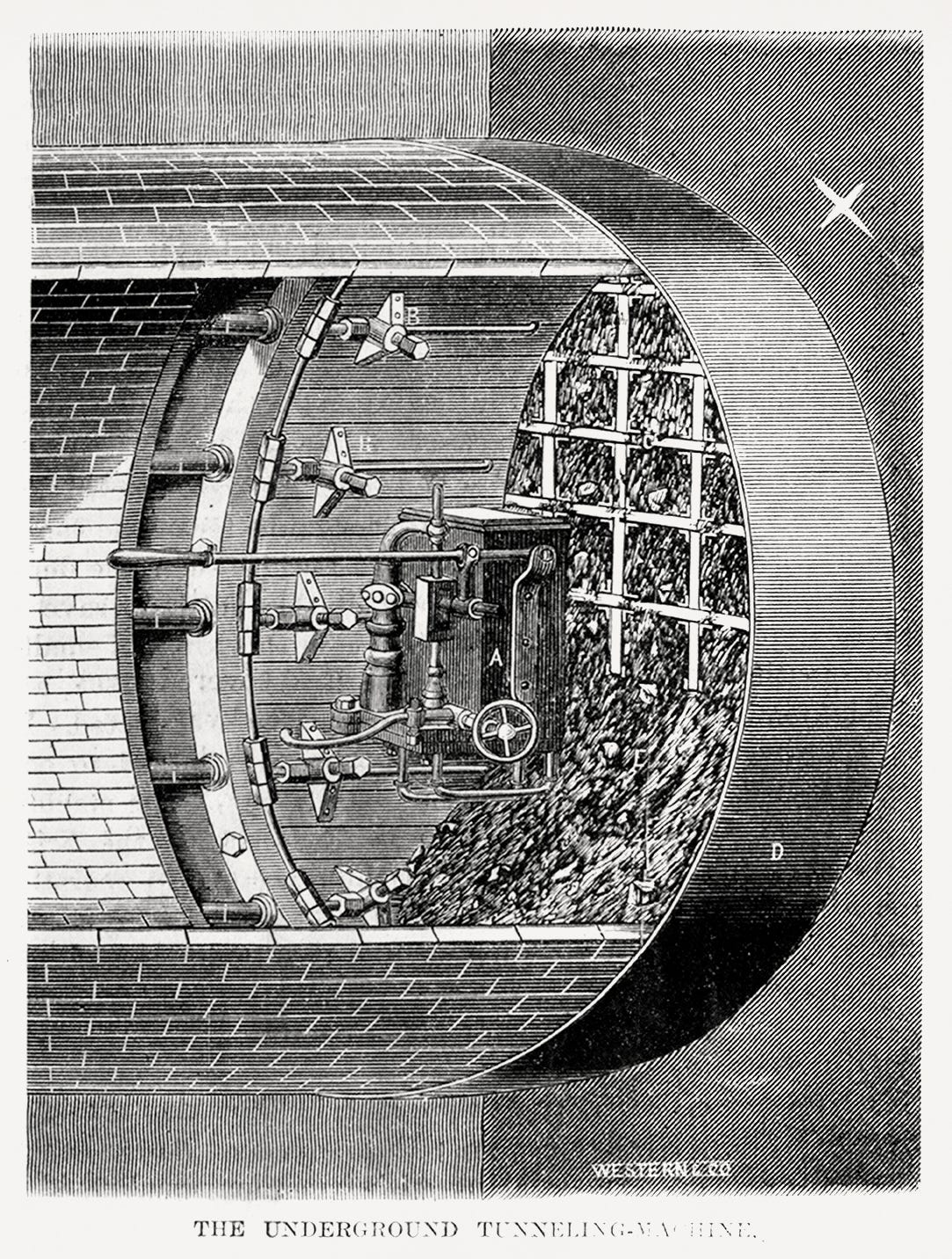

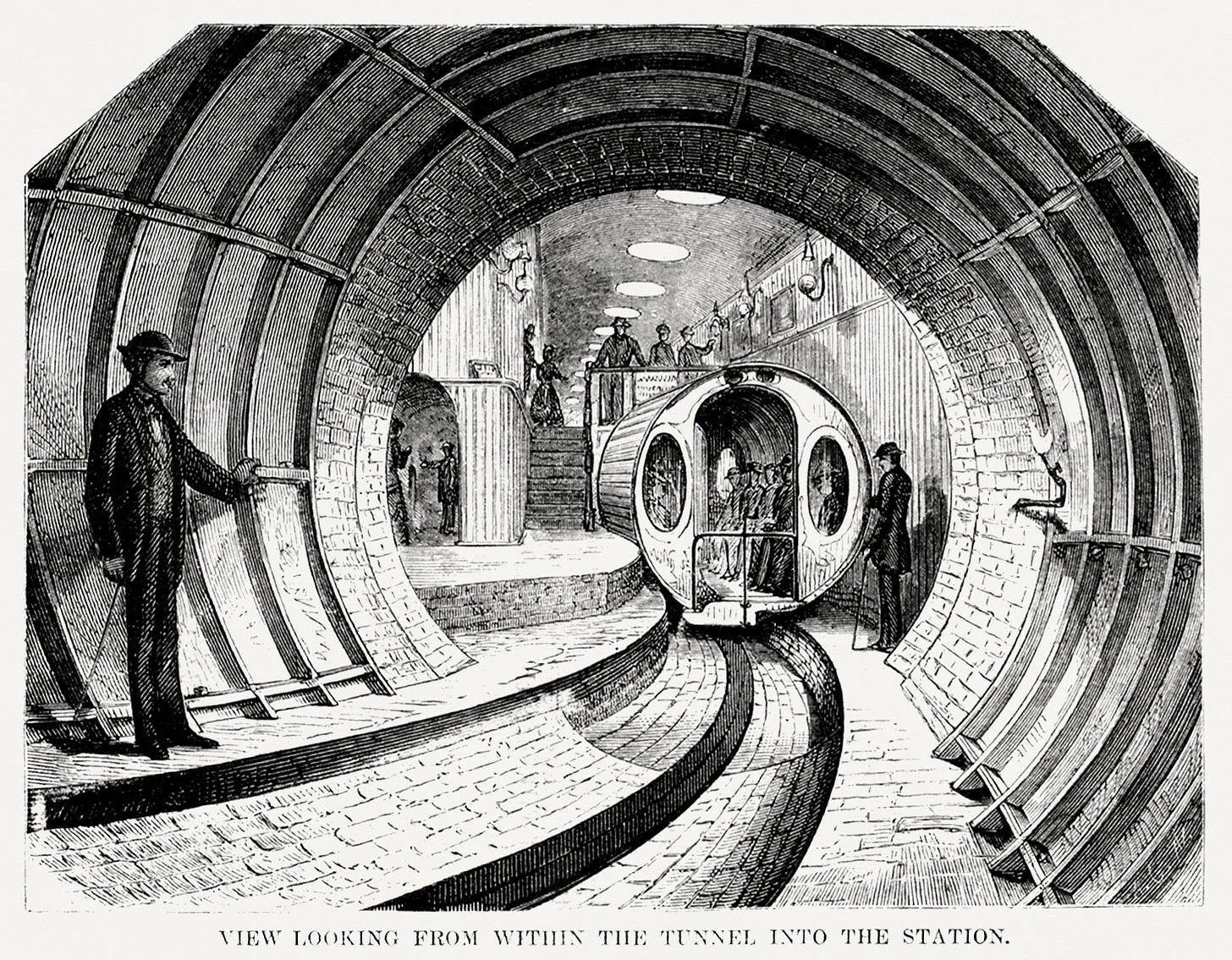

These images of the Beach Pneumatic Transit, also known as the Broadway Pneumatic Underground Railway, are all in the public domain. They were originally published by the New York Parcel Dispatch Company and can be found on Raw Pixel. The Beach Pneumatic Transit was the first attempt to build an underground public transit system in New York City.

Illustration of the new post office & proposed Broadway underground railway (1872)

§§§

Interior Design of the Pneumatic Passenger Car (1872)

§§§

The Underground Tunneling Machine (1872)

§§§

View of The Station from The Tunnel (1872)

Four Things To Listen To

Galeet Dardashti - Adonai Hu Ha’elohim

§§§

Errollyn Wallen - In Earth

§§§

Heart - Magic Man

§§§

Justin Hiltner - Wildflowers

Four Things About Me

When I was in fifth or sixth grade, I interviewed one of my maternal great-grandmother’s sisters—I think it was Aunt Becky—for a family history project. She told me about her family’s experience with pogroms in Romania. (My grandmother, if I remember correctly, was the first member of her family born in the States.) In particular, Aunt Becky told me about the Christian family across the street who hid them in the basement whenever a pogrom was happening. At the time, I didn’t fully understand the depth of the courage that family showed, but it made a real impression on me nonetheless. It is not overly dramatic to say that if that family hadn’t shown the courage it did, my great-grandmother and her sisters might never have been able to come to the United States. More than that, though, that family’s courage has stood for me as an exemplar of what my own response to hatred and oppression ought to be. I may not always live up to that standard, but it is the one to which I try to hold myself accountable.

§§§

Fifteen years ago, I was teaching a summer composition course in which there was a student from India who stayed after class one day to speak with me about writing. I don’t remember the particulars of the conversation, but my antennae definitely went up when I saw how anxious she became when she looked at her watch and said her husband was waiting for her in the car. It was clear to me that she was worried about more than making him wait a couple of extra minutes. She came back to speak with me again—she told me she told her husband it was to discuss an essay she was having difficulty with (in fact her writing was quite good)—and it was during that meeting that she revealed to me that she wanted out of her marriage because her husband was abusive. Then, one day, when she’d asked again to see me after class, she told that her husband had threatened to kill her. Not here in the states, she said, but while discussing a trip he was planning for them back to India, he showed her a gun he had and started talking about how she might be in control in America because there were laws here that tied his hands, but he would be in control once they were back in their country. She understood him to mean in no uncertain terms that he planned to murder her once they were there, and that he expected to be able to do so with impunity. When she told me this, I put her in touch with the South Asian Women’s Association (SAWA). She could not use her cell phone to make the call, since her husband checked her phone regularly. The only place she said she felt safe calling, because it was the only place where she could be guaranteed some measure of real privacy, was on campus. She didn’t want to use the phone in my office, though, because her husband might come looking for her if she took too long getting to the car after class. Instead, I brought her to another office I had access to, and she made the call from there. SAWA helped her with the information she needed about her legal rights as a non-citizen victim of domestic violence. That information helped her feel strong enough to call on some friends who helped her get away from her husband. We were in touch on and off during and after her divorce and I wrote letters of recommendation for her once she decided on a career path, but it’s been more than a decade since I last heard from her. I hope she is doing well.

§§§

In 2017, a central Asian student in an ESL class I was teaching came to my office to discuss the essay I had assigned for that week. What started out as a discussion about how to organize her paper, however, became very quickly a discussion of how meaningless she thought school was, since she knew she wasn’t going to be able to do anything with her degree. Her parents, she said, were desperately trying to marry her off. She was the youngest child in her family, had graduated high school the previous year, and her parents, especially her father, wanted to make sure she did not fall prey to the “corrupting freedom” American culture offered women. Her parents had been trying to arrange a match for her for some time, but while the men they chose were all well-established and would be able to take good care of her, they were also much older than she was, boring (in her estimation), and, according to her, really, really ugly. It wasn’t, she explained, that she was opposed to marrying someone her parents chose for her, and she definitely did want to marry someone from her own faith and culture, but—she’d either been born here or had come here when she was very young—she wanted the man she married to have at least a little bit of the Americanized identity she had. She went on to tell me that she’d dated a few men from her background—always behind her parents’ backs, of course—but even though they seemed to be pretty thoroughly acculturated, they all exhibited some version of what she experienced with the one man she thought might be someone she could marry. As soon as they officially became a couple, he started checking her Blackberry to see whom she was calling and who was calling her. It reminded her of her father, she said, who, though he’s threatened to do so, hasn’t yet gone quite that far. She was angry and frustrated, shamed by both her own helplessness and the fact that she’d been sneaking around behind her parents’ backs—so much so that she started saying things like, “Maybe I should just end it all.” When I asked her what she meant by that, she said she’d been thinking she should just surrender to her parents, that since marriage was the only way she could ever have any semblance of her own life, maybe she should just marry one of the men they chose for her and then figure things out from there.

One of the reasons she felt so isolated and helpless, she explained, was her American friends’ inability or unwillingness to understand why she didn’t just break with her parents. Some of them apparently told her she had only herself to blame since she did not run away. (Some friends!) I think she may have said I was the first person in whom she confided, but I am not sure. What I do know is that she told me she’d chosen to trust me because I’d talked in class about living in Korea at a time when arranged marriages were still the norm and where it was as culturally unacceptable to go against one’s parents as it was for her to go against hers. A year or so after this conversation, I heard she’d gotten married. I have no idea what the circumstances were, but I remember thinking at the time that it didn’t matter whether the man she married was imposed on her by her parents or whether he was a man she’d chosen, the one discussion she and I had opened a window for me I would not otherwise have had about what compulsory heterosexuality is like from a woman’s perspective. (The article I’ve linked to is in some ways dated—the first sentence is a good example—but it’s worth reading nonetheless.)

§§§

For a while, I was teaching evening classes till late enough that I sometimes did not get home from work until around 11 PM. One night, I passed a couple talking about thirty feet from the entrance to my building. The woman was leaning with her back against the driver’s side front window of one of the vehicles parked on the street. Her bag was on the car’s roof. The man stood in front of her, close enough that she couldn’t easily move away, with his right hand planted firmly on the line where the front and rear doors met. His posture, though, seemed more intimate than threatening. They were arguing in Spanish and their voices were low, so I took them to be just what they appeared to be, a couple having a disagreement, and I walked by without giving them a second thought. As soon as I walked up the steps leading to my building, though, the man shouted something in Spanish and I heard what sounded like his hand slamming, flat and hard, against the roof of the car they’d been leaning on. I stopped and listened for about ten seconds. It was quiet. I peaked around the tree that was blocking my line of sight. They were standing more or less as they had before, and when nothing else happened, I assumed he’d had a momentary outburst and started to walk into the lobby. As soon as I did so, though, he started yelling again, and this time the sound of shaking metal made it clear that he’d hit the alternate-side-of-the-street-parking sign that was right next to where they were standing. I stepped back onto the street just in time to see them walking past. He had her purse in his left land and her upper arm in his right. Her shoulders were slumped, and, to my eyes, it looked like she’d decided she had no choice but to let him lead her away. Then, as if he felt my eyes on the back of his head, the man turned around, let go of her arm, handed her purse back to her, and took a few steps towards me. The invitation to provoke him into more than words was more than obvious in his tone, “What are you looking at?” I didn’t answer. He took another step towards me. “Mind your own fucking business,” he shouted, loud enough that I can’t imagine the people on the first couple of floors of my building didn’t hear. “This has nothing to do with you, okay?” Again, I didn’t answer. “Look this is not between you and me,” he yelled.

“Then you don’t need to hurt her,” I responded in as quiet and calm a voice as I could.

“What the fuck? I’m not hurting her.” He waved his hand dismissively. “Just go home.” It was an order he expected me to follow, not a reassurance everything was okay. Then he turned back to the woman, retrieved her purse, and hung his arm over her shoulders, pulling her to him and saying something in her ear as they walked down the block, neither of them looking back in my direction. I watched for another ten seconds or so. They looked like any other couple walking home after having been out for the evening, so I went upstairs, made myself a cup of tea, and watched a little television to unwind before going to bed.

There’s a lot to say about this scenario and maybe I will one day write the essay that teases it all out. What goes through my head every time I think about it, though, is whether or not the situation really was abusive—it would be unfair not to acknowledge that it might not have been—and how close I might have come to being assaulted. If I had to guess, I’d say the man was about ten or fifteen years younger than I was—this happened when I was in my fifties—and looked like he could do a lot of damage without very much effort. Thankfully, that did not happen, and I continue, even all these years later, to hope the woman was as safe as he wanted me to think.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

A poet and essayist, I write about gender and sexuality, Jewish identity and culture, writing and translation. My goal? To make connections that matter. I also help other writers do the same.