Writing News

In the kind of synchronicity that usually happens only in fiction, a piece that I wrote on February 4, 2020 was published exactly five years later, on February 4, 2025. I confess that I am not sure whether to call it a poem or a piece of creative nonfiction, but it’s called “On February 4, 2020, instead of watching Donald Trump deliver his State of the Union Address…” Michael Broder, publisher of Indolent Books, accepted it for the series he is calling “Second Coming: A poem-a-day series in creative response to the threats posed to our democracy by the incoming presidential administration.” You can read the piece I am talking about here.

Four Things To Read

The Bookstore Book: A Memoir, by Ron Kolm

Consisting of a sequence of vignettes in both prose and poetry that capture one man's life in books, The Bookstore Book is a guided tour through a slice of New York's literary scene that usually doesn't get much attention. In the same way that, for example, office staff are the people you go to if you want insight into a business' true inner workings, Kolm shows in this book that, at least during the years he worked in the city's independent bookstores, the bookstore staff plays a similar role. From the quirky anecdotes he shares about his encounters with the likes of Allen Ginsberg, Philip Roth, Kathy Acker, Patti Smith, and Charles Bukowski to the only-in-New-York moments that he captures without adornment or sentimentality, Kolm allows us into what it was like to live a writer's life of and in books before Borders, Barnes & Noble, and Amazon changed irrevocably that way of life. Reading Kolm's book made me nostalgic for the days when I could immerse myself in St. Mark's Bookstore or the Spring Street Bookstore, or even the Scribner's bookstore that used to be on Fifth Avenue the way you immerse yourself in a warm and welcoming pool of water, always leaving with some drops still clinging to your body, even if those drops were all you took away with you. The Bookstore Book draws it emotional power, as well as its depth, from the apparent artlessness of Kolm's writing, whether in poetry or prose, an effect that takes a lot of work to achieve. The Bookstore Book is worth reading, if only for the history, but it also contains small moments of aesthetic pleasure that continue to grow even after you put the book down.

§§§

"What Happened to the Black-Jewish Political Alliance?," by Rachel Cohen

[In Black Power, Jewish Politics: Reinventing the Alliance in the 1960s, Marc Dollinger shows that despite their vocal support for the African American struggle, most Jews were not risking their livelihoods for black freedom in any real way. As Dollinger writes, Southern Jews embraced Dixie and were overwhelmingly silent on civil rights. Northern Jews took pride in their support for justice, but “most experienced that movement from the safety and comfort of their living rooms, where they read about direct-action protests in the newspaper or watched it on television.”

Cohen offers in this brief essay a discussion of Dollinger’s main thesis, which is succinctly captured in the essay’s subtitle: “Challenging the sanitized history of blacks and Jews during the Civil Rights era.” The narrative of the Jewish community’s role in the Civil Rights movement that I learned was precisely the opposite of the one summarized in the above quote. I was taught that Jews were uniformly and unanimously united in their (often heroic) proactive support of the movement, in both word and deed. It does not surprise me—and this is what Cohen says Dollinger’s book shows—that the full story is more complex than that, on both sides of the alliance. Indeed, reading Cohen’s piece made me think of the one (and, sadly, failed) attempt that I know of on my campus to form a Black-Jewish alliance. It was in the early years of my career and the planning and inevitable accompanying politics happened far above my head, so there’s a lot I don’t know about why we failed. Two things, however, have stuck with me. I am not sure if the first one was an insight at which people arrived at the time or if it’s an idea I am imposing in hindsight, but, as I recall, the initial call for an alliance did not emerge from a collaboration between Jewish and Black faculty, but rather from a proposal issued by Jewish faculty. Whether or not this was the intent, in other words, the proposed alliance was a product of the Jewish faculty’s vision and it was structured as an invitation to Black faculty to enter the Jewish faculty’s space—a sure recipe for misunderstanding and failure. The other thing I remember is trying to discuss with a Black colleague after our one and only meeting why his use of the term “philosemitic” was problematic. I don’t recall precisely how he used it, but I can still hear my colleague telling me that Louis Farrakhan was not antisemitic, but that my support of “my people,” right or wrong, was something to be respected. I’ve put Dollinger’s book on my list of books to get.

§§§

What Water Knows, by Jacqueline Jones LaMon

The title of this book recalled for me a quote by Toni Morrison, “All water has a perfect memory and is forever trying to get back to where it was.” Water journeys in this volume from the taps in the first poem from which “it’s rare to find people who drink” to, in the last, that which, “stand[ing] apart/from ourselves,” we choose not to drink, substituting instead “Bordeaux—that strong, heady red we pour into stemware,/to escort us away from our lives,” thereby escaping, or so we hope, the fact that water knows “the inside of insides of us.” Functioning as metaphor, symbol, allegory, and as itself, water weaves its way through these poems like a river winding its way through issues that are central to our time—racism, for example, or addiction, or climate change—as well as those that are inescapably part of what it means to be alive among people: commitment, betrayal, loss, renewal, love. There is an implicit narrative that runs through the poems, or so it seemed to me, but the poems do not reveal the story itself. Rather, they invite us into the speaker’s thought process as she works through what the narrative confronts her with. This, for example, is the beginning of “The Latitude, The Longitude, And A Third Axis Called Time:”

When you change your environment, you change

your opportunities—or so said my son, endorsing

our move across the nation to a place he didn’t know.

And we went, and worlds shifted, and we thought

him so wise, to have sensed that only parts of our thinking

were true, the rest only habit, relentless and dogged.

We never know why the family has to move or from where. Instead, the poem becomes a meditation not on the move itself, but on the storm the family travels through in silence and how that silence, especially when entered into together, “holding hands and breathing,” is a kind of preparation for the inevitable “encroaching storms” that life throws at us.

“The Latitude, The Longitude, And A Third Axis Called Time” is also an example of a sonnet-like form LaMon uses throughout the book. It’s one that I have never seen before, and I am guessing she invented it: three five line stanzas followed by a single, sixteenth line, set off from the others like the final couplet in a Shakespearian sonnet. Most often, this line is composed of a three-item list, the first two items of which in some way “sum up” elements of the previous three stanzas, while the third opens the poem up into entirely new territory. The last line of the poem I am discussing here, for example, is “The desert scorch. The flooded streets. The minefields of the night.”

I am glad I read this book.

§§§

"On the 'Victims of the Victims:' Revisiting Edward Said’s ethical humanism in the context of the Gaza genocide," by Ussama Makdisi

Today, after 76 years of meticulous cruelty that touches every aspect of Palestinian life throughout historic Palestine, as Israel carries out a genocidal campaign in Gaza that, at the time of writing, has killed an estimated 64,260 Palestinians and wounded tens of thousands of others, I am unsettled by the question: Does the “victims of the victims” still make sense as an ethical-historical formulation?

Makdisi is referring to Edward Said’s assertion—he quotes here from Said’s book The Question of Palestine—that “empathizing with ‘the disastrous problem of anti-Semitism’…offered some way out of the morass of competing victimhood” that so often disrupted (in Said’s time) meaningful and productive discussions of what to do about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict. “This intertwining of empathy,” Makdisi writes, “reflected [Said’s] conviction that the fate and futures of Palestinians and Israelis were inevitably tied together by the question of Palestine.” The gist of Makdisi’s essay is the question of whether, given not only Israel’s genocidal campaign in Gaza, but also the fact that the “liberal West has categorically refused to view Palestinians as victims of any moral or historical significance,” Said’s call for empathy for what Jews have suffered throughout the centuries still “makes sense as an ethical-historical formulation.”

It’s an important question. There may have been a time, certainly after World War II, but even going back to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the Jews who settled Palestine could reasonably be seen as victims fleeing antisemitic oppression, regardless of whether or not, or even to what degree, they embraced Zionism as an ideology. I am reminded as I write this of June Jordan’s acknowledgment in her 1985 essay, “The Blood Shall Be a Sign Unto You: Israel and South Africa,” that

[f]or anyone Jewish…Israel must represent, on a level of sensibility inaccessible to argument and/or entreaty, an absolute imperative, a refuge, a place of sanctuary, a final deliverance out of the deserts of horror.

Certainly, that was the version of Israel’s significance with which my early Jewish education was saturated, and it’s not hard to understand why Jews worldwide might feel that way just forty years after the Holocaust (understood not only as itself, but also as the epitome of a centuries long history of antisemitic violence and oppression). Nor is it hard to understand why someone might think that acknowledging that emotional reality would open the door to a corresponding Jewish empathy for the situation of the Palestinians. After all, if you see someone suffering the way you have suffered, isn’t the logical course of action to do what you can to end that suffering? Speaking for myself, one of the reasons Jordan’s essay was so formative for me was that it was the first time, ever, that someone who wasn’t Jewish had asked me to look at the facts of what Israel was doing to the Palestinians, while simultaneously acknowledging the legitimacy of my feelings-at-the-time about the need for Israel’s existence.

Given the genocidal extent to which Israel has victimized the Palestinians since October 7th, Makdisi asks if it still makes sense to extend that kind of empathy to Israeli Jews. It’s a good and fair question, as long you don’t make the mistake of conflating Israel and Israeli Jews with the Jewish people worldwide.

Four Things To See

A Broadside by Liora Ostroff

You can read the artist’s statement here:

§§§

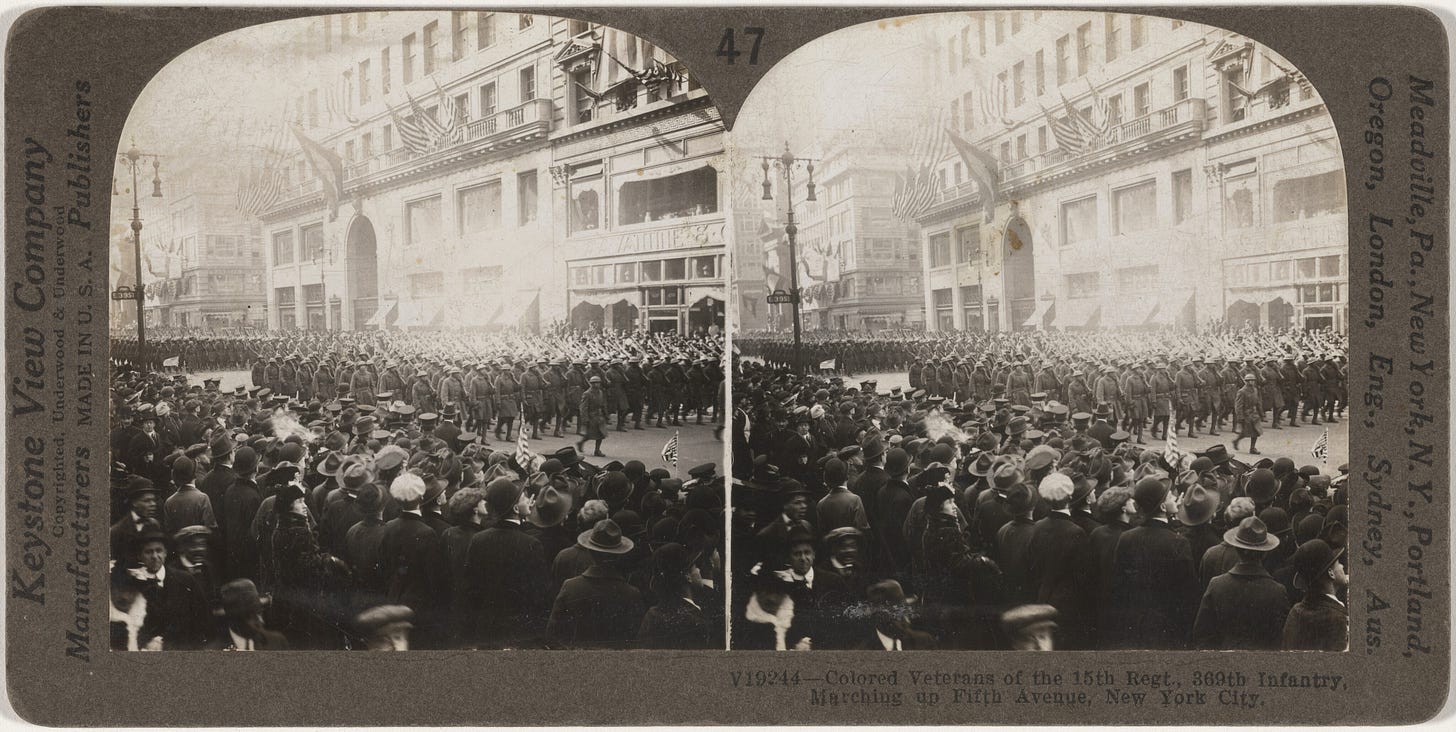

Colored Veterans of the 15th regiment, 369th infantry, marching up Fifth Avenue, New York City, 1919

§§§

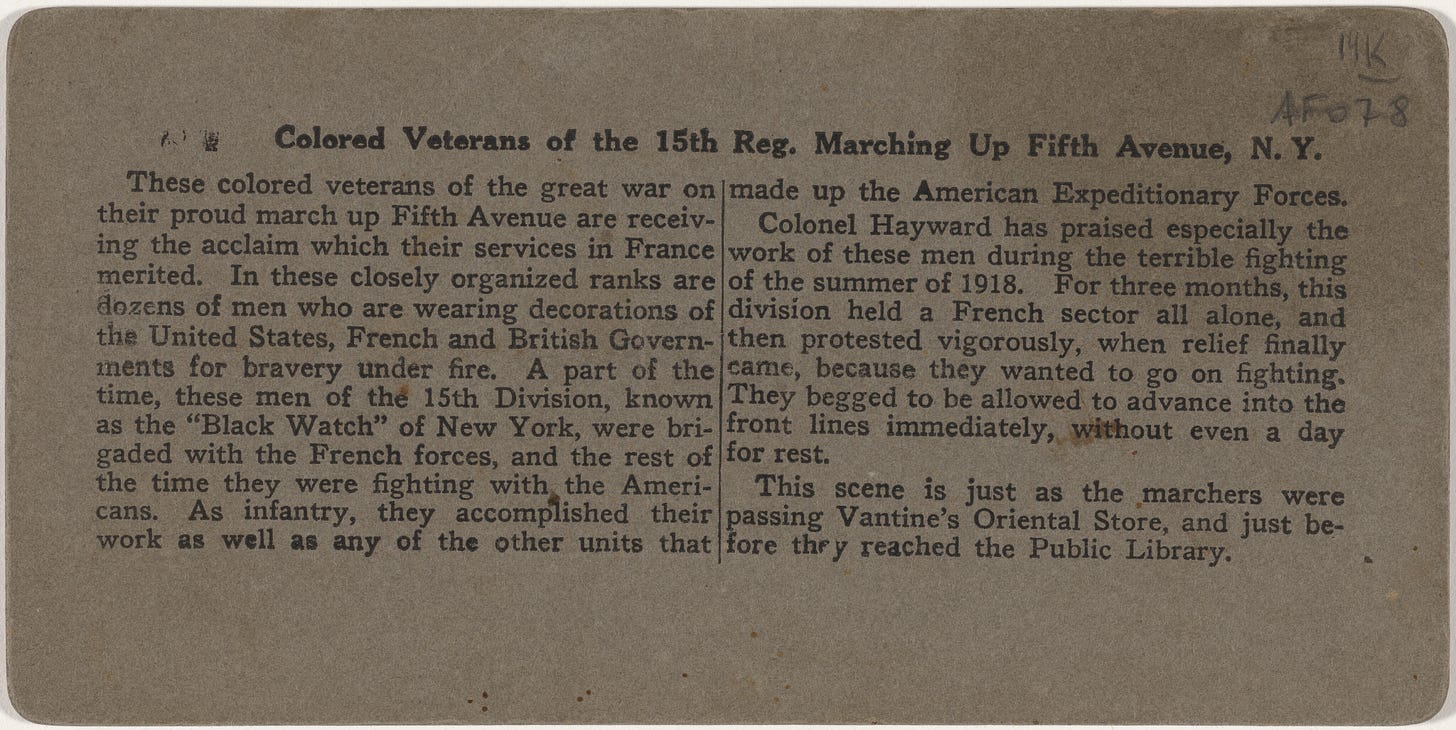

Black Power Poster from National Museum of African American History and Culture

by Alfredo Rostgaard

§§§

Supper Time

Four Things To Listen To

Billie Holiday - Strange Fruit

§§§

Curtis Mayfield - People Get Ready

§§§

Mavis Staples - We Shall Not Be Moved

§§§

Nina Simone - Mississippi Goddam

Four Things About Me

Case of mistaken identity #1: In March 1998, Prairie Schooner published two poems of mine, “Kashrut” and “You Will, Of Course, Assume It Is For You,” which eight years later became part of The Silence Of Men. To have not just one, but two poems published in a nationally recognized literary journal was a major accomplishment, of course, but to share space in the journal with poets whose names I knew—Linda Pastan, Robert Pack, Albert Goldbarth, Ruth Stone, and, as a translator, Marilyn Hacker—was affirming for me in ways I don’t think I knew I needed until that moment. Shortly after the issue of the journal came out (Vol. 72, No. 1), I got a message on my answering machine—remember those?. A male voice said, “Hello, Richard Newman, this is Richard Newman” and went on to explain that he, too, was a poet and that he thought we should probably talk. When I called him back, he explained that his friends, thinking that my poems were his, had been congratulating him for getting published in Prairie Schooner. Since he knew he hadn’t written the poems, he’d called Hilda Raz, who was editing the journal at the time and whom he knew through his work as editor of River Styx Magazine, to get my phone number. We chatted for a while and then he brought up the question of how to avoid this kind of confusion in the future. Since he already had an established presence in the literary world and I did not, I told him that I would start using my middle name when I published. I have this vague memory that he told me he would start using his middle name as well, but he never did. In any event, that is how I came to be known, for the first time in my life, as Richard Jeffrey Newman.

§§§

Case of mistaken identity #2: I remember I was sitting at my desk at home grading papers, when I got a phone call on my landline. I picked up the receiver and the voice on the other end said, "Is this Richard Newman?" When I answered in the affirmative, he asked another question, "Did you recently purchase new living room furniture from Macy's?" Now I was suspicious. How did he know this, I asked in return. "I think they accidentally sent me your bill," he responded and he read out to me the items listed there. Sure enough, it was the living room furniture my wife and I had purchased not too long before. Somehow Macy's had sent my bill to his Cambridge address. What made this case of mistaken identity memorable, however, is that the Richard Newman to whom I was talking turned out to be a well-known professor of African American Studies at Harvard University. According to this Newman's Wikipedia page, his work "reshaped both African-American History and Early American History by unpacking the ways in which revolutionary era blacks, in particular AME Church founder Richard Allen, contributed as ‘founding fathers.’” I knew none of that as we chatted on the phone about our respective careers, however. After I looked him up, though, I ended up buying two of the books he edited, Everybody Say Freedom: Everything You Need to Know about African-American History, which he edited with Marcia Sawyer and African American Quotations, of which he is the sole editor. I have used each one often and I always remember fondly how I came to discover this other Professor Newman and his work.

§§§

Case of mistaken identity #3: I was standing in the hallway talking to a colleague, when I got a call from my wife. "Where are you?" she wanted to know. I told her I was in Bradley Hall, which is the building on campus where my office is located. "Are you sure?" she wanted to know, the edge in her voice giving me a clue that something was wrong. "Yes, I'm sure," I told her, and I gave her the name of the colleague I was talking to—I don't remember who it was—who then gave me, as you might imagine, a strange, quizzical look. “Go some place private where we can talk," my wife said, so I went back to my office and closed the door. A doctor had just called her, she said, telling her to come "pick her husband up" from a psychiatric ward somewhere in the Bronx. When she told this doctor he couldn't be talking about her husband, because he had left for work earlier that day, he didn't believe her, and his tone, she said, made it clear that he thought he was talking to a heartless woman who was perfectly happy to let her husband stay in that psychiatric ward. Obviously, the man in the ward wasn't me and so I assumed my identity had been stolen. What actually happened, however, as I learned later, from the doctor in charge of the institution where that other Richard Newman had been admitted, was that he had been brought by police to the emergency room of the hospital in my neighborhood because he was suffering a psychotic break. When the hospital admitted him, because his name was the same as mine, and because his birthday was the same as mine, my records popped up on the computer, since I had been there at some point in the past. As a result, whoever admitted him just assumed he was me. The situation was ultimately resolved, but for a brief while I felt like I was living in the middle of a short story written by Franz Kafka.

§§§

There was a bully in the neighborhood where I grew up whose name was also Richard. He was enough older than me that we almost never crossed paths, but his younger brother, also a bully, crossed paths with me quite a lot. I was about twelve or thirteen years old at the time. I do not remember, and it may be that I never knew, why this other Richard approached me one day in the courtyard outside the building where I lived. I was hanging out with a group of my friends when he walked up to me. I’m pretty sure his brother was with him. “I hear,” he said, “your name is Richard. Is that true?” I told him yes. “Well, that’s my name too, and it belongs to me, so you can’t use it anymore. Figure out what else you want to be called, because if I find out after this that people are still calling you Richard, you’re going to be very, very sorry.” I vaguely recall trying without success to reason with him, and I was scared when he left. I don’t remember him ever bringing the subject again, but I did walk around for a while with a low-level of anxiety thrumming through me, especially when I saw his brother. In the end, nothing ever came of it, but it was a formative experience nonetheless, in that someone more powerful than I tried to erase my identity, or, more accurately, try to get me to agree to erase my identity to satisfy his whim.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

It All Connects is for anyone who grapples with complexity—of identity, art-making, culture, or conscience—to make a difference in their own life and, potentially, in the life of their community.

Member discussion