Writing News

I have, finally, completed a draft of the manuscript of poems that emerged from a daily writing practice I sustained from New Year’s eve 2019 until the first week of 2021. It’s taken me four years to sort through, hone, and revise the material, and I am very happy with the result. Some of the poems have been published. “Sunset,” for example, appeared in the lovely journal humana obscura; “The People of Gaza Keep Dying,” appeared on New Verse News, and “On February 4, 2020, instead of watching Donald Trump deliver his State of the Union Address…” was published in Michael Broder’s Second Coming series—on, ironically enough, February 4, 2025. Other poems have appeared or are forthcoming in publications like Poets of Queens 2, The Scene, and the literary journal published by the International Human Rights Arts Movement.

During the initial stage of this project, I set myself only one constraint: that while I did not care how little I wrote on any given day, I would not write beyond the limit of that day’s page in the Lechtturm1917 page-a-day planner I’d bought. Once I was ready to start sorting, honing, and revising, though, I increased those constraints to three:

- I would work on the poems only in the order of their composition;

- If it turned out that the way to make a particular day’s writing work as a poem was to combine it with material from another day’s output, I would only take that other material from something else I’d written in the same month; and,

- In terms of content, while I would allow myself to go as far back into the past as I wanted/needed, I would not introduce anything into a poem that happened after the original day, or if that were not possible, the original month of composition. I made two exceptions to this last constraint, “The People in Gaza Keep Dying” and “In That Moment of Change.”

I wrote the poem that became “The People in Gaza Keep Dying” in January 2020 in response to the experience of reviewing Contestable Truths, Incontestable Lies, by Steven Sher. Sher’s book is a deeply racist, proudly anti-Palestinian, Orthodox Jewish justification of the Jews’ claim to the Land of Israel and to the legitimacy of Israel as a Jewish nation state. Particularly disturbing is a poem called “Bombing Gaza” that, in light of the devastation Israel has wrought there since October 2023, could be called prophetic.

Before October 2023, I wasn’t sure how exactly I wanted to focus the poem. Once Israel began to bring Sher’s “Bombing Gaza” to life, however, it felt irresponsible not to connect the poem explicitly to current events. I decided to give the poem a title that would do this work instead of changing the text of the poem itself.

The detail I added to “In That Moment Of Change” is its dedication to the memory of my friend Veronica McGinley, who was murdered by her husband in April 2021. At that time, the poem had still not fully taken shape. It fills me with a deep, deep sadness that she will never read it, which is why I am dedicating this book to her.

Four Things To Read

After The Operation, by Elizabeth T. Gray, Jr:

When they come for you, when the unfamiliar roar comes, and a sudden opening, and light pours in, when what had kept you safe, what had always been, is breached, pried open, and light pours in, what do you want to have been writing then?

Gray, a poet and translator, was diagnosed at 68 with a benign tumor in her brain that she elected to have surgically removed. After The Operation is her poetic chronicle of that experience. The emotional weight of the book is carried by its metaphors, which transform the speaker’s mind into “an uninhabited coast” that needs exploring. Similarly, the year becomes a puzzle the speaker takes apart every morning. Birds appear throughout the book, though whether they are symbols the speaker conjures, allegorical figures she uses, or hallucinations she actually sees, or all three at once is not clear. Either way, though, they come across in the reading, along with the metaphors I mentioned above, as the product of a mind trying to make sense, make meaning through poetry, of an experience that might otherwise remain solely in the realm of the clinical.

The most moving part of the book comes at the end of the January 20, 2022 journal entry—which, coincidentally, is my birthday—from which the passage that I quoted above is taken. Read in the context of the brain surgery Gray went through, it is about what happens, what it means, when the physical, structural integrity of who you are is violated. Read in the context of today’s politics, though, it is about far more than that. It is the ultimate question any writer needs to answer: Is what you pursue in your writing meaningful enough that when “they” come for you, whoever or whatever “they” happen to be, it will be precisely the work you want to have been stopped in the middle of, work that mattered enough that they had no choice but to stop you from doing it.

§§§

Unveiling the Domestic Mind: Persian Women Poets on the Self and the Other, by Fatemeh Minaei:

This article compares, contrasts, and discusses poems by women from across the millennium of Persian poetry. It foregrounds the differences while not presuming any ontologically stable contrasts. It also does not claim to identify any underlying sociopolitical or economic factors behind these changes since such claims would lead to repeating common knowledge or making uneducated guesses. This article instead focuses on how the Persian female poet has become not only possible but normal.

The last line of that paragraph, which is from the introduction, took me back to article and books I read in the 1980s and 90s about women’s poetry in the United States, in particular Alicia Ostriker’s Stealing The Language: The Emergence of Women’s Poetry in America—though this is a purely impressionistic association, since it’s been thirty years at least since I read Ostiker’s book.

I don’t know enough about Iranian literature in general or Iranian women poets in particular to say anything at all intelligent about the individual artists Minaei refers to in her essay, but the trajectory she traces is, broadly speaking, a familiar one. Starting with the classical poets, Minaei documents attitudes ranging from Somehow she managed to be a poet despite being a woman to the line by a male satirist which said that men hearing the ghazals of a poet known as “the beauty of [her] time” would think they were “composed by the vulva.”

Minaei also—and this also made me think of Ostriker’s book—talks about the difficulty women poets faced trying to carve out a sense of female identity using language that was inevitably androcentric, a process made in some ways more complex by the fact that Persian does not have gendered pronouns. Most importantly, though, Minaei documents the ways in which Iranian women poets, by claiming language for themselves are increasingly accepted, as she says, as “normal,” not curiosities. This is an interesting essay, worth reading.

§§§

Maimie Pinzer: July 14, 1885–1940, by Romy Shoam:

At the age of thirteen, Pinzer spent several nights at a man’s house, which prompted her mother to request her arrest—a grave response, perhaps reflective of their difficult mother-daughter relationship. When Pinzer was imprisoned at the police station in the Philadelphia City Hall, she exchanged sexual favors with a prison guard in order to be allowed out of her cell. At her judicial hearing the next morning, her mother and uncle, who had molested her throughout her childhood, accused her of being an incorrigible child. Pinzer was transferred to the Moyamensing Prison, then sent away to a Magdalen Home, a reform institution for girls, for a year. From this period onwards, she learned how to use prostitution to ensure her security.

My source for this article is The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, a resource I discovered only recently. The details of Mamie Pinzer’s life that are recounted in this entry come from a correspondence she maintained with Fanny Quincy Howe, an American essayist and novelist who was also a member of the Boston economic and social elite. That correspondence was published in a book, The Mamie Papers: Letters from an Ex-Prostitute, edited by Ruth Rosen, in 1977.

The encyclopedia entry gives a brief overview of what one working-class Jewish woman’s life was like in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Of particular note is The Montreal Mission for Friendless Girls, which Pinzer founded and ran out of her apartment in 1915. “Pinzer,” the article states, “wanted to target English Protestant and Jewish women because they were excluded from the charity work administered by the Catholic Church.” She was also opposed to using the word Friendless in the name because of its negative connotations. “Her personal approach…informed by her own experience, differed greatly from the standard treatment of prostitutes by social workers and reformers at the time,” concentrating more on providing material help to the women, rather than the moralizing, spiritual “guidance” they usually received.

This article was, for me, a peek into a slice of history—Jewish, women’s, working class—that I would not otherwise have gotten. It’s work a look.

§§§

Teens Are Forgoing a Classic Rite of Passage, by Faith Hill

Research indicates that the number of teens experiencing romantic relationships has dropped. In a 2023 poll from the Survey Center on American Life, 56 percent of Gen Z adults said they’d been in a romantic relationship at any point in their teen years, compared with 76 percent of Gen Xers and 78 percent of Baby Boomers. And the General Social Survey, a long-running poll of about 3,000 Americans, found in 2021 that 54 percent of participants ages 18 to 34 reported not having a “steady” partner; in 2004, only 33 percent said the same.

In this article, along with a companion piece she wrote called “The Slow, Quiet Demise of American Romance,” Hill explores a phenomenon that, as someone who has not dated in more than thirty years, feels very, very distant. Still, I was intrigued by the way this piece worked its way through the subject, from the possibility that what we’re really talking about is a difference in labels—“situationship” vs. “relationship” to research that suggests young people might be better off not dating in terms of their leadership and social skills, for example.

Other aspects of this topic Hill explores, include “a real [negative] shift in how comfortable American are…with emotional intimacy;” the gender-political divide, in which men are shifting more to the right and women are moving to the left; and the way in which even “under conditions of a gender cold war, [while] many girls might get on fine[,] boys could suffer more,” because boys are much more likely not to have as many close friendships as girls and are therefore more likely to be at a deficit when it comes to the kind of social and emotional skills/maturity that is required for a successful romantic relationship.

That gender gap has implications for a lot more than just romance and is very much worth paying attention to.

Four Things To See

In honor of Norouz, the Persian New Year, here are “four things to see” connected to Iran. All images are from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City and are in the public domain.

Cheek Piece from a Horse Bit in the Shape of a Winged, Human-Headed Quadruped

This piece dates from the 8th century BCE and is probably from Lorestan, Iran.

§§§

A Stamp with a Pahlavi Inscription

This stamp is from the Sassanian period, which dates from the 3rd to the 7th century CE. Pahlavi is an extinct language, also known as Middle Persian.

§§§

Frontispiece of Rumi’s Masnavi

This frontispiece depicts a lively scene in which mounted hunters use swords, bows, and arrows to pursue their prey. An inscription dates the completion of this manuscript in 1488-89 CE. Broadly speaking, the Masnavi teaches moral philosophy and mysticism.

§§§

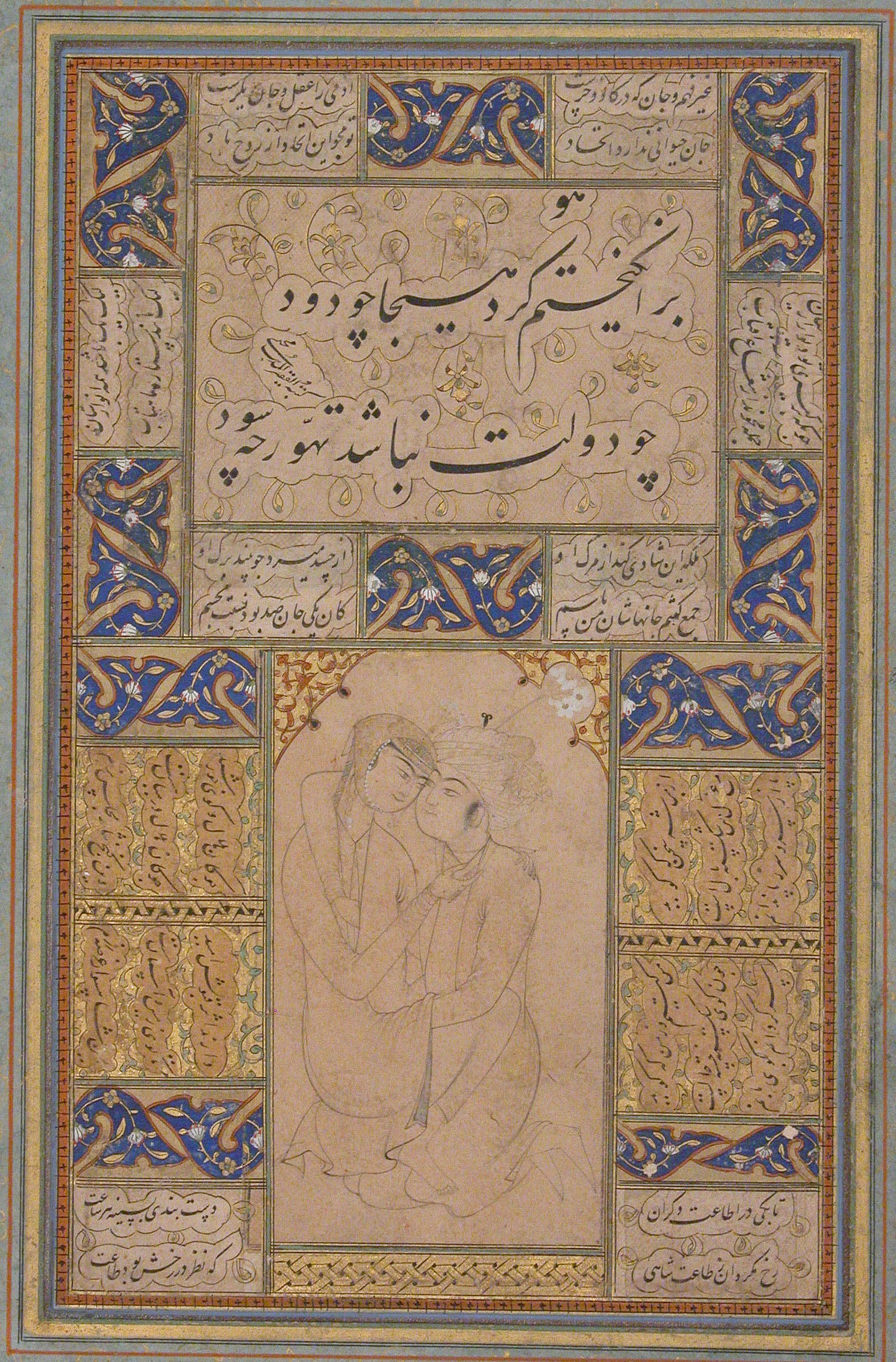

Young Lovers Embracing

Dating from the 16th century CE and probably from Qazvin, Iran, this album page consists of cut‑out panels of calligraphy in nasta'liq script alternating with panels of illumination, all surrounding a drawing of an amorous couple. The delicacy with which the lovers are rendered makes for an unusually sensual image. The drawing is surrounded by lyrical and mystical verses.

Four Things To Listen To

Mitra Sumatra - Helelyos

Also in honor of Norouz.

§§§

Ani DeFranco - Little Plastic Castle

§§§

Allison Miller’s Boom Tic Boom - Live at the Kuumbwa Jazz Center

§§§

Richie Havens - Freedom

Four Things About Me

Recently—I don’t know why—I was thinking about a course I took as an undergraduate with Professor Rose Zimbardo at Stony Brook University, and I remembered a paper I wrote for that class about the three caskets in The Merchant Of Venice. In particular, what I remembered is the fact that Professor Zimbardo asked in the margin about which scholars I’d read in order to arrive at one of the points I made. At first I thought she was implicitly criticizing me of plagiarism, but then I realized she intended the comment to mean that she was impressed an undergraduate had bothered to do that kind of research. The irony was that I hadn’t done any research at all. I’d arrived at the insight on my own. (I only wish I could remember what it was.) I could not, however, recall the paper in any more detail than that—not surprising, since I wrote it in the 1980s—so I went to my computer, sure I would find it among the undergraduate and graduate essays I turned into PDF files about ten years ago. It wasn’t there.

§§§

Among the papers that were there was “The Troubadours And Medieval Hebrew Poets Of Muslim Spain,” which I wrote for a history course with Professor Helen Lemay. I remember this paper very well. Towards the end of the semester after I took the class, I decided I wanted the paper back, so I contacted Professor Lemay to find out how I could go about getting it. She told me it was still in the box where she’d left it, but when I went to the History office to retrieve it, I found it with another student’s name on it. Someone had stolen the paper and handed it in as his own. Ironically, he got a higher grade than I did, either an A to my A- or an A to my B+. I somehow managed to find out which dorm this guy lived in, but when I confronted him, he was completely unrepentant, claiming that he’d stolen my work because his sister had been in the hospital all semester and not only didn’t he have time to do the work, but he also couldn’t afford to fail the class. I think I may have believed him because of how indifferent he was to the idea that, if I reported him, which I threatened to do, he could be kicked out school for academic dishonesty. I think I remember talking to Professor Lemay about this, and I think I remember her not being so interested in pursuing charges, though I could be totally wrong about that. Either way, I decided not report him on the off chance that he really was telling the truth. Now that I’m a professor, I would never let someone get away with that kind of academic dishonesty, no matter how dire their circumstances, but that fact does raise the question of what the compassionate response would be.

§§§

The other paper I enjoyed revisiting is called “The Problem of Form.” I wrote it for I-don’t-remember-which literature class during my first semester in Syracuse University’s Creative Writing MA program. This is the (edited-to-remove-my-graduate-school-hemming-and-hawing) thesis statement, “There are also…certain questions about form…which the notion of form as an extension of content does not provide a way of exploring.” I was frustrated—and my frustration was a young poet’s frustration—by the circularity of the scholarly approach to form that seemed only to treat it as an extension of content, ignoring, or at least that’s how it seemed to me at the time, the fact that a poet’s formal choices are only successful if they result in poems, regardless of whether not the choices themselves are driven by content. In other words, and I still stand by this, I was working through for myself the notion that a poet’s formal choices have to work first as form, as music, as structure before their relationship to content can even begin to matter in an artistic/aesthetic, much less scholarly, sense.

§§§

This is what Professor Linda Shires wrote in response to that paper:

Your essay is interesting as a personal investigation. In other words I think poets like Eliot, for example, would agree with much of what you say—indeed have said it themselves. It isn’t new. But your argument—your manifesto—engages. It is strongly argued and you are widely read. Insights “along the way” are rich [and] informed.

The major weakness of my application to Syracuse’s program, it was pointed out to me by two faculty members, one a poet and one a scholar, was that I didn’t seem to have my feet planted firmly in one camp or the other; and since this was in the 1980s, during what I came to think of as “the theory wars,” the scholar who was my graduate advisor—not Professor Shires—minced no words in telling me what he thought when I very timidly asserted that I thought of myself as a poet first. This is practically a direct quote, “If you want to commune with your muse, that’s your business, but I thought you came to Syracuse to learn something.” Professor Shires’ comments, on the other hand, unprompted, affirmed for me the validity of my interest as a poet in the question of form. She gave me permission to pursue my academic work at Syracuse as a “personal investigation,” not a scholarly one—something my advisor and my other non-creative writing professors tended to see as inappropriately rebellious—and I am very grateful to her for that.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.

Thanks for reading It All Connects...! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

A poet and essayist, I write about gender and sexuality, Jewish identity and culture, writing and translation. My goal? To make connections that matter. I also help other writers do the same.