Writing News

Sonia Alland’s and my translation of “The Words,” by Salvador Espriu, was published in Black Lawrence Press’ tr. review of translations.

§§§

My poem “In That Moment of Change,” which I wrote in memory of my friend Ronny, who was murdered by her husband in 2021, was published by the International Human Rights Arts Movement in The Evolving Gaze, an issue of their quarterly publication devoted to questions of manhood and masculinity. They’ve gathered an impressive range of work, in terms of country of origin, age, gender, and more. It’s a publication definitely worth a look on its own merits. My poem is on page 93.

§§§

Back in 2021, I took part in Queensbound, poet KC Trommer’s audio project for bringing poetry into public spaces, both online and in the physical world. The concept is simple. Each poet chose a subway stop in Queens, NY and incorporated it into a poem that they then recorded for inclusion on the site. My stop was Elmhurst Avenue on the R line. If you go to the Queensbound website, you can listen to my poem by clicking on the station, or you can listen on Soundcloud, or—and here is why I am telling you about this now—you can check out the Queensbound podcast, which recently went live. My poem is in the third episode, but I hope you will consider checking out all the episodes.

Four Things To Read

Nasir Khusraw: The Ruby of Badakhshan, by Alice C. Hunsberger:

If Nasir Khusraw [1004-between 1072 and 1088] is less well-known today, even in Iran, than other Persian poets such as Sa‘di, Khayyam, Rumi or Hafiz, other travel chroniclers and historians such as Ibn Battuta or Ibn Khaldun, and other philosophers such as Ibn Sina, al-Farabi or Nasir al-Din Tusi, this may in part be due to his devoted allegiance to the Ismaili Shi’i faith…Also, rather than composing love poems or mystical odes…Khusraw focused largely on ethical and moralizing poetry, admonishing the reader to attend to the task of spiritual improvement in place of chasing after the baubles of this material and materialistic world.

As you might guess from that brief quote from the Preface, this book is mostly for people in the field of, or with an informed interest in, Persian Studies. Alice Hunsberger gave me a copy in 2011 when we met at a talk she was giving about the book, which I attended because my own translations of Saadi (which is the non-diacritical spelling of Sa’di) had brought me marginally into a circle of writers and scholars engaged in research about and the translation of classical Persian poetry. A lot of what Hunsberger has to say, I have to confess, went over my head. I simply do not know enough about Islamic, much less Ismaili Shi’i, theology and epistemology. I did find very interesting, if I understood it properly, Hunsberger’s discussion of Khusraw’s conviction that the intellect is the only truly authentic way to pursue both a righteous life and knowledge of God, an idea that sounded very much like the emphasis on learning Torah, on using one’s intellect to understand Jewish law and what it means to be a Jew, that I was taught when I was in yeshiva. I was also fascinated by Hunsberger’s discussion of Khusraw’s travelogues. One thing that stuck out to me—in the vein of “the more things change…”—was the fact that, in 11th century Cairo, the buying and selling of drinking water was big business; and I especially appreciated learning about Khusraw’s critique of court poets who, these are Hunsberger’s words, “use their art to weave the praise of unworthy kings, telling beautiful lies for worldly wealth.” Finally, Hunsberger’s study is also interesting as a formal exercise in the writing of biography. Khusraw’s life and work present interesting problems for a biographer to solve and Hunsberger does so in a way that’s worth engaging with separate and apart from whether the book’s content is specifically your cup of tea or not.

§§§

The SAVE Act’s Impact on Women Voters Isn’t a Coincidence. It’s Voter Suppression., by Beth Lynk:

Make no mistake: The SAVE Act is not going to “save” anything. This legislation would create unnecessary barriers to registering to vote in every state. It would require all voters to provide proof of citizenship documents in person when registering to vote or updating their registration—provisions that effectively end online, automatic and mail-in voter registration. Women who change their name after marriage or divorce would face unnecessary barriers to registering to vote.

While the SAVE Act seems tailor made to make it more difficult for poor people and people living in rural areas to vote, along with a host of other groups living in one way or another on the edge, its potential impact on women is particularly insidious because it demonstrates how the right can attack women without having to name what they’re doing as an attack on women. The issues this legislation could create for women who changed their name after marriage, or who didn’t change their name back after divorce, is redolent of the time when banks could either refuse women credit cards in their own names or require them to have a male cosigner. That practice ended only in the 1970s. More importantly, though, it’s crucial to recognize the context in which that practice existed. Back then, for example, pregnant women had no protection against being fired from their jobs; it wasn’t until 1975 that women in all 50 states could serve on juries; and spousal rape was not yet a crime. The consequences of the SAVE Act for women, intended or not (though it’s hard to conclude that they were not intended), feel very much like a step back in that direction.

§§§

Trump Is Selling Jews a Dangerous Lie, by Michael S. Roth:

As the first Jewish president of a formerly Methodist university, I find no comfort in the Trump administration’s embrace of my people, on college campuses or elsewhere. Jew hatred is real, but today’s anti-antisemitism isn’t a legitimate effort to fight it. It’s a cover for a wide range of agendas that have nothing to do with the welfare of Jewish people.

I’ve said this elsewhere, but I will say it again. It has become commonplace, on the left at least, to use the genocidal destruction Israel has wrought in Gaza to justify dismissing, minimizing, and/or trivializing Jews’ concerns about antisemitism, as if concern about both those things cannot coexist in the same moral imagination. What I admire about Roth’s op ed is that he manages to call out the confidence game Trump and company are trying to run on the American Jewish community while barely even mentioning what is going on in Israel and Palestine; and—at least as I read his essay—he does this in two ways. First, by not revealing his own stance on Israel and Palestine, implicitly driving home the point that antisemitism is an issue for all Jews—Zionist, non-Zionist, anti-Zionist, whatever. Second, he makes clear through the force of his examples that antisemitism is not primarily about what’s going on now in Israel—even if Israel’s behavior may be what triggers some antisemitic acts. Regardless of where you stand on Israel and Palestine, this essay is worth reading.

§§§

We Underestimate the Manosphere at Our Peril, by Rachel Louise Snyder:

It took under nine minutes for TikTok to offer troubling content to their fake 16-year-old boys, which later included explicitly anti-feminist and anti-L.G.B.T.Q. videos. Much of the content blamed women and trans people for the standing they believe men have lost in the world. More extreme content appeared within 23 minutes. Male supremacy videos intersected with reactionary right-wing punditry within two or three hours.

Back in the mid-aughts, I blogged pretty regularly at Barry Deutsche’s site Alas. Alas was, if I remember correctly, the first feminist blog run by a man, and I was very happy to contribute to that effort, both in my own posts and in the comments I contributed to the discussion. (As a side note, Alas is now primarily a platform for Barry’s political cartoons, which are definitely worth checking out.) A non-trivial portion of the discussion had to do with what was being written and promulgated on men’s antifeminist blogs. The term manosphere, an obvious play on blogosphere, emerged around that time and it quickly became an umbrella term for a number of different online communities that nonetheless have in common the goal of promoting some version of traditional masculinity, an often virulent antifeminism, and misogyny. What was once clearly a fringe of internet culture, however, has become more and more mainstream. “We live in a new world,” Snyder writes, “where words like ‘women,’ ‘gender’ and ‘trauma’ are banned or limited in research studies. Phrases like ‘women are property’ and ‘gay people are mentally ill’ are no longer violations of conduct at Meta.” Snyder’s essay is also worth reading for the links she’s embedded. Just about every one leads to something that is worth knowing about this issue.

Four Things To See

Orpheus Charming The Animals

By Josias Murer II (1564-1630). Murer, who was part of a family of artists living in Zurich in the fifteen and sixteen hundreds, became the exclusive glass painter of Zurich's city hall in 1591. He was fully occupied with this distinguished commission until 1614. Murer was trained by his father, Jos Murer, with whom he often worked. He also frequently worked with his well-known brother, Christoph Murer. In addition to his designs and paintings for the Zurich city hall, Murer created numerous stained glass panels of coats of arms for churches and city halls throughout the region. Little else is known about this artist. The image is from Getty and is in the public domain.

§§§

A Manuscript Page from “On Poetry and Our Relish for the Beauties of Nature,” by Mary Wollstonecraft

You can read the full essay here. The image is from the New York Public Library and is in the public domain.

§§§

Llewllyn And His Dog

This image is also from the New York Public Library. It’s from a children’s book illustrated by the Dalziel brothers. The lines are the first verse of the poem “Llewellyn And His Dog,” by the Honorable W. R. Spencer. Llewllyn the Great was a medieval Welsh ruler who, through a combination of war and diplomacy, dominated Wales for 45 years. The dog’s name was Gelert.

§§§

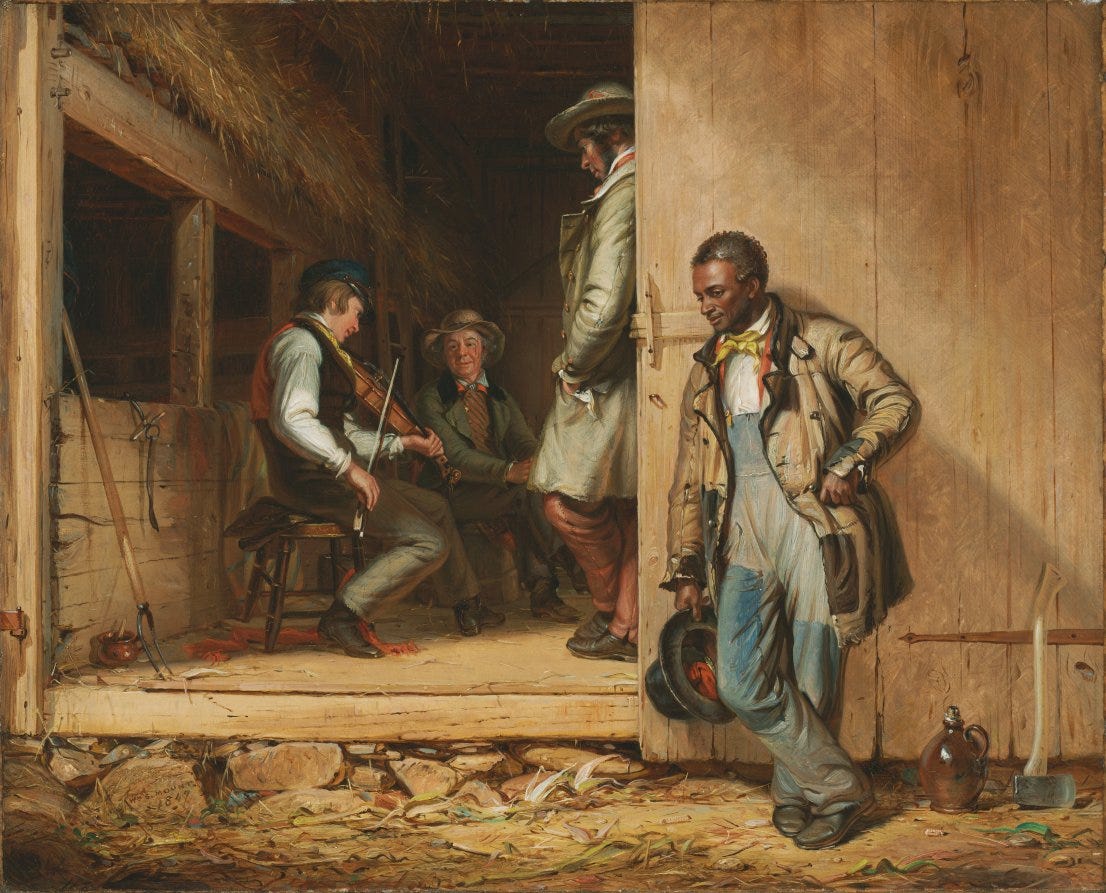

The Power of Music (1847)

By William Sidney Mount (November 26, 1807 – November 19, 1868). Mount was a 19th-century American genre painter. Born in Setauket, New York in 1807, Mount spent much of his life in his hometown and the adjacent village of Stony Brook. During that time he achieved fame in the U.S. and Europe as a painter who chronicled rural life on Long Island. He was the first native-born American artist to specialize in genre painting. Mount was also passionate about music and a fiddle player, a composer and collector of songs, and designed and patented several versions of his own violin which he named the “Cradle of Harmony.” This painting, set in rural Long Island before the Civil War, presents an African American laborer listening intently to a fiddle tune enjoyed by white men. While a love of music unites the figures in a bond of shared humanity, the two races occupy different spaces--one inside, one outside, both separated by a barn door--effectively symbolizing the pronounced divisions in America at the time.

Four Things To Listen To

Lou Rawls - Stormy Monday (with Stanley Turrentine)

§§§

Bobbie Gentry - Ode To Billie Joe

§§§

Oded Tzur - The Three Statements of Garab Dorje

Garab Dorje was the first human to receive the complete direct transmission teachings of Sutra, Tantra and Dzogchen. The circumstances of his birth are shrouded in different interpretations, with some accounts describing a miraculous birth by a virgin daughter of the king of Uddiyana.

§§§

Mickey Katz - Duvid Crockett

You can find the footnoted lyrics of this song here.

Four Things About Me

We own an orange Le Creuset cast iron oval baker that, along with a matching orange skillet that went the way of the world years ago, was given to me nearly four decades ago by a man named Herbert, who was passing them along to me from his friend Michael, who had died of AIDS not long before and for whom Herbert had been a primary caregiver. Herbert, a friend of my grandmother’s, was a gay man who had either converted to Roman Catholicism or had recommitted himself to his religion—I don’t remember which—and, following the logic that only homosexual acts were sinful, not being homosexual itself, he had become celibate. Caring for Michael, I think, was not only Herbert’s way of being of service to someone in need—if I remember correctly, Michael’s family had disowned him—but also a kind of penance for the sinful (in his and his god’s eyes) life he had previously led. I don’t remember why I went with Herbert to visit Michael the one time I met the man, but I remember a gaunt, red-haired man with a well-groomed beard lying in bed with the blanket pulled up to the middle of his chest. I don’t remember how long we stayed or what we spoke about, or how long after that visit Herbert presented me with the cookware, but I do remember what he said when he gave it to me. Since Michael had no family to leave anything to, Herbert explained, he wanted to make sure that the few belongings that constituted his estate went to people who meant something to him. I, though I have no idea how, had made such a strong impression on Michael that one time we met, that he included me in this group. “I went to see Michael the day after you met him,” Herbert said, “‘That,’ he said—Michael was referring to you—‘is a good man. I want to give him something.’” I still think of Michael every time I use his gift to cook.

§§§

I’ve been thinking about paper grading a lot lately, mostly because I am retiring this year, and each set that I grade brings me closer to the one that will be—because I do not intend to teach in my retirement—the absolute last one.(I know: talk about burying the lede, right? But more about that in a moment.) What I’ve been thinking is that almost no one I know who is not an academic, really understands the degree to which grading essays is emotional labor; and even among those who are academics, I don’t know many who fully recognize that the emotional labor is different when writing is what you’re teaching, as opposed to when you are teaching a content. I’m not talking about the anger and frustration you feel at half-assed work or at students who don’t know how to follow directions, or at least I’m not talking primarily about that, and I certainly am not suggesting that the grading of English papers is therefore in a class of its own as a condition of employment. Difference does not have to mean hierarchy. Rather, I’m talking about the labor involved in accompanying, guiding, mentoring, students not only on the intellectual journey their work represents, but also on the journey through language, the wrestling with language, their writing cannot help but be. Because when writing is what you’re teaching, you can’t avoid the fact that even the students who do half-assed work have put their vulnerability on display; and I do believe that because this vulnerability foregrounds their relationship to language in a way that, say, a research paper for history class does not necessarily do, working with them touches on their sense of self, on the state of their self-esteem, in a different way as well. I don’t have much else to say about this right now. I just wish it was something more people recognized.

§§§

Why am I retiring? The initial trigger was an incentive offered by the college where I work. Every advisor I consulted, some professional, some people I trusted, advised me that it would be a mistake not to take it. Once I started contemplating even the possibility of retiring, however, an inescapable realization began to dawn on me: I no longer have patience for the eighteen-to-tweny-or-so-year-olds who make up the majority of my students, and because I don’t have that patience anymore, teaching does not fulfill me the way it used to. When I tell most people that, they nod knowingly and begin to commiserate with what they think I mean, that students today are so much worse than they used to be: less respectful, more entitled, too immersed in their phones, unwilling to read, to think for themselves, too transactional about their education, too indifferent to the world around them. I don’t want to deny that there is some truth to these observations, though I think many of them boil down to the fact that we are a generation or two apart, but I do not think that there are any inherent, essential differences between the students of today and those from thirty-six or twenty-six or even sixteen years ago. I see in the young people sitting in my classrooms today the same levels of maturity, of cognitive development, of commitment to their own intellects as I did when I started. They write, more or less, the same essays, make the same mistakes, and give the same excuses as college freshman and sophomores have always done. I, I realized as I thought about not teaching them anymore, am the one who has changed. When I started teaching, I was young enough that, at least for some of the older students in my class, if I had not been their teacher, we could have been hanging out together at a bar. I truly enjoyed the challenge of showing why learning to write competently mattered. Now, I am old enough to be their father and, if their parents are young enough, even their grandfather. I will not say I do not care, but I have come to understand that the challenge is just interesting to me anymore. More than that, though, I realized that after thirty-six years I am ready—no, that’s not strong enough, I realized that I need to do something different. I don’t know exactly what that is yet, but I am looking forward to finding out.

§§§

One of the strangest things about being the most senior person in my department is that none of the people who were my colleagues when I got hired are full-time faculty anymore. Some, even these thirty-six-years later, are teaching adjunct, but most are gone from the college completely. It makes me feel in a way nothing else does just how much institutional memory I carry, but it also makes me realize how much I have forgotten. Not too long ago someone posted a picture of members of the department from twenty-five or thirty-years ago, asking if someone could name the people in the picture. I remembered all of their faces, but I got almost every one of their names wrong.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list.

A poet and essayist, I write about gender and sexuality, Jewish identity and culture, writing and translation. My goal? To make connections that matter. I also help other writers do the same.